Cast of Wonders 616: Worse than a Wolf

Worse than a Wolf

by Wen Wen Yang

The sound of the metal grinding against the whetstone reverberated up my arms. My father was sharpening his ax, preparing for the day’s work. “I invited Mu to dinner tonight,” he said.

I shuddered.

Mu was a woodsman whose family came from a neighboring village in China and had settled in the same rural town in Oregon a decade before my family. How happy my family was to hear our dialect! It almost made this foreign country feel safe.

“Why?” I stirred the pot on the wood stove and inhaled the smell of comfort: ginger and garlic. I was cooking the wonton soup my grandmother liked. My cousins and I had often fought over who made better looking wontons and always lost to our grandmother. “He visited just last week for the Mid-Autumn Festival.”

“He brought those double yolk mooncakes,” my grandmother recalled as she folded a clean shirt into a crisp square in the far corner of the room. She was a short woman and every year seemed to lose another inch.

When my parents first arrived, Mu had persuaded his boss to hire my father to clear the trails and the smaller brush. It paid better than the fish processing plants and you didn’t need to speak the language to trim overgrown hedges. My mother had been glad my father no longer reeked of fish.

Mu had found a small cottage at the outskirts of town large enough for my grandmother, my parents and me. We no longer had to squeeze into a space meant for one family with my aunt, uncle and three cousins.

Not long after we moved into the cottage I first noticed the paw prints in the morning dew, and the feeling of being watched when I hung the laundry to dry. My aunt warned me to leave an offering in the woods, because we were the ones entering the wolf’s territory. I told her that the wolves here spoke a different language than the wolves back home. I had learned their language faster than I had learned English. My aunt understood the Chinese wolf’s howls, too, though we never spoke of it around my father or her husband. Appeasing a wolf’s temper seemed easier than easing her husband’s.

After I saw the mother wolf with her cubs one night, I left her a cut of fat from a pork belly. She had three cubs. The next morning, I heard her scolding them.

“Don’t eat that!” she snapped. “Humans will poison you.”

“It’s safe to eat,” I whispered out my window. The mother wolf’s ears pricked, but she led her cubs into the undergrowth. The pork fat was gone the next night. We didn’t have much to spare after that first offering.

In the kitchen, my father asked, “What’s wrong with you? You used to like Mu.”

It was true. Mu had congratulated my father on his industrious daughter with the neat stacks of clean laundry that pleased our customers. Even my cautious mother had trusted him. He had brought flaky egg tarts, still warm from the bakery.

I cannot eat them anymore.

My eldest cousin was unquestionably more charming, more talented. She could make the guzheng sing. And yet Mu had made me feel beautiful, despite my inheritance of my father’s wide nose and my mother’s crooked teeth. He had complimented my thick black hair while his hair was thinning at the crown.

Then he made me feel broken and dirty.

There was a drawer of his gifts that I could not bear to look at. I left them with my cousins.

“He makes a good living,” my father continued, turning his ax. “Winter is coming. Don’t you want a warm hearth, a full belly?”

Being hungry was preferable to Mu’s company. He had large hands that I could not swat away like a biting fly. Now my father was offering to put Mu’s hands around my throat.

“If I’d had a choice,” my grandmother interrupted as she tied together the bundle of fresh shirts. “I would have picked a man who could read and write.”

I curse the person who taught my grandfather how to gamble instead of how to read. Two years before my family crossed the ocean, he lost the money we had been saving for the voyage. The next summer, a tiger mauled him to death. My grandmother found his body, his blood staining the rice field.

“In English and Mandarin,” I agreed, dividing the wontons among the three bowls.

“It’s a struggle to live with an ignorant man.” Grandma sucked her teeth. “My mother told me that it’s better to be with a smart man who beats you than a foolish man. As if those were my only choices.”

How many generations of women have endured a life instead of enjoyed it?

“This brings in some money.” I gestured at the clean laundry. “You couldn’t take care of Grandma alone.” He could not deny filial piety, not when it was cooked into my marrow.

My father grimaced. I had hurt his pride.

“I will find work like my biao jie.” My oldest cousin was a bookkeeper at the tailor’s shop. Better than washing and ironing for pennies.

“You don’t have the head for numbers like she does.” My father sucked his teeth.

Embarrassment stung my cheeks.

“Besides, she’ll marry the tailor’s son soon enough. You wouldn’t attract a man as wealthy as the tailor before the end of the summer.”

My father thought the monster chasing me was winter’s cold and hunger, when it was actually the man he had allowed into our home. I could not bear to tell my father that he had trusted the wrong man. I was afraid of what he would do with his ax, of what this country’s justice would do with a murderous foreigner.

“Don’t rush your daughter,” my grandmother scolded. “What family wouldn’t want an obedient daughter-in-law?” Her words burned through me. Obedient. Like a dog. Told to stay quiet, to not tell anyone.

I could feel my tears coming, my bile rising, and retreated outside to harvest the spinach from the garden. The breeze tore at my hot cheeks. Tears gathered in my throat. I would rather go hungry and scavenge in the woods, I wanted to scream. I would rather my clothes smell of rotten fish than Mu’s sweat. Some nights, I woke from nightmares of Mu’s stubble scratching my cheek, his breath in my ear. I would lie awake, refusing to return to my dreams, until I heard my father shuffle into the kitchen.

I slashed at the weeds, pretending the knife was a claw, until my eyes were clear, my chest heaving. If I only ate weeds, would I still need to marry Mu?

I knelt on the ground where we had buried my mother. When the fever took her, I felt so angry that she had left me behind. Did she know now what I couldn’t find the words to say?

When I came back inside, my father was rubbing camphor oil into his shoulders.

“I had two children by the time I was nineteen.” My grandmother washed the greens I harvested. “But they do things differently in this country.”

“Where are your glasses?” my father asked.

She sucked her teeth. “I can’t find them because I can’t see!” Her glasses cost nearly a month of laundry work plus two weeks of my father’s wages.

I went into her room and found the glasses between her mattress and the wall. They had fallen back there last month too. The lenses were scratched but my grandmother had insisted they were still fine. If I married Mu, could I buy my grandmother new glasses?

“They grow legs when you aren’t looking,” she exclaimed when I presented them to her. She blinked up at me with her magnified eyes and called me by my mother’s name. I didn’t correct her. My father never said my mother’s name anymore.

“There’s some taro in the woods, ready for harvest,” my father said abruptly, washing his hands. “Over by the river.”

“Taro, here?” my grandmother asked. I had missed the starchy sweetness.

“I’d recognize those leaves anywhere.” My father nodded toward the nearly empty pantry. “Harvest it all. That could be dinner for everyone.” With Mu joining us, we had to stretch our food with what the woods could offer.

We ate breakfast carefully, maneuvering around the bundles of customers’ clothes. My father retrieved his ax just as the morning sunlight touched the curtains. “Take care of your grandmother. Beware of the wolves,” he called over his shoulder as he left.

I brushed my grandmother’s hair. Her fine white hair was almost transparent. Perhaps next week I would need to trim it before it hung over her hooded eyes. While living all together, my family had decided my hands were steadiest and I had become the family haircutter. When I shaved my uncle, I had often thought of pressing the razor a touch too deep along his throat.

“Grandma, your ears are so large.” I untangled the ends of her hair.

“Big ears are very lucky. Like the Buddha’s. I could hear the cows asking to be milked, the chickens shouting ‘good morning!’” While my aunt and I could hear animals like my grandmother, it seemed to have skipped my father.

For the rest of the morning, Grandma and I cleaned, shoulder to shoulder, to prepare to receive Mu. Did she already imagine me married to Mu, depending on his money as long as I was obedient? How else could I fill the pantry, buy my grandmother new glasses?

“I’ll look for that taro.” I pulled on the coat my mother had made for me, desperate to escape the impending dinner.

I’d started to outgrow my previous coat, a hand-me-down from my eldest cousin, two winters ago. The sleeves had crept up my arm and the wind stole the warmth from my belly. My mother had started sewing a new coat for me. Then she became too sick to help with laundry. Then she was too exhausted to work the sewing machine. When she died, the red coat lay unfinished across her lap, needle and thread still in her hand.

My grandmother had finished the buttons and topstitching, but it was my mother’s care I remembered when I wore it.

“Be careful of the wolves,” Grandma called after me. I heard her lock the door.

I balanced the empty basket on my hip and trekked through the woods. Dry leaves crunched under my boots and swirled around me. The birdsong that had sounded so strange when we first arrived had now lost its novelty. Dark, loud crows had replaced cranes.

I searched for red berries. If I could find a large, mature ginseng root, I could sell it to the herbalist. Perhaps that would be enough to keep me out of marriage for another six months.

Up the side of one tree was a dark crop of wood ear fungus. I trimmed off pieces, careful to keep them intact. My grandmother had taught me how to search for it, how to cut it from the tree. When I first harvested them, I had whispered my secrets into those dark misshapen ears. Perhaps, when my family ate them, they would know what Mu did. But my grandmother only said that I had to wash them more carefully next time, there was still dirt in hers.

Clusters of mushrooms grew along the fallen trees. Some were pristine white bulbs with rings along the stems. If they were dangerous, how could I keep a morsel from my father or grandmother’s bowls? My grandmother had not taught me how to spot poisonous mushrooms or dangerous men.

At the bottom of the hill, I found the taro. Large spearhead leaves hung over the river. I dug and scraped the roots from the corms with my spade.

The basket was nearly full when I heard another set of footsteps. Had Mu tracked me? My breathing became ragged, my palms sweaty. I grasped the dirty spade.

Then the wind changed direction, and I recognized the scent of a wolf: decaying crops and black pepper.

I turned, my body burning with fear under the red coat. If they could wash the blood out of it, perhaps my middle cousin could wear it next.

The wolf approached, shoulder blades sharp under the skin. Her belly was gaunt, empty of food for her and her pups. There were spots where her fur had fallen out, exposing her pink skin. Her tail was as thin as a whip.

“So small.” Her voice was reedy, disapproving. She sounded like my aunt when browsing the fruit stalls too late in the day. The wolf sat in front of me, one front paw lifted in consideration. “Can you even run, little one? Do you not fear wolves, girl?”

“Of course I do, Madam Wolf. Everyone can see your true nature from your fangs to your claws.” I bowed my head in deference. “Every villager warns their children to come in before dark. We shutter our windows and bolt our doors.”

The wolf’s head rose, elegant and haughty. “Have you met anyone more terrifying?” She asked.

“There are sneakier creatures,” I answered. “There was a man who was invited into my home. I set a place for him at the table. He smiled with bright white teeth in a mouth that knew how to charm everyone. His hands had clean trimmed nails. But when no one was looking, he unleashed something worse than a wolf.”

Her lips pulled back, exposing her fangs. “I would like to see this man who is worse than a wolf.”

“He hid it so well,” I whispered. “You wouldn’t know until it was too late.” I wiped my eyes with the coat sleeve. “He is large, and boasts of killing moose.”

“He has taken my prey.” Her ears perked. She licked her lips. “Have you taken my prey, girl?”

“No, Madam Wolf.” I pointed at the basket. “I have only dug up the taro. But this man, he will be your dinner.”

Her dark eyes focused on me. “And what will you give me in return, girl, for taking down this formidable man?”

I wore no jewelry and carried no coins. What would a wolf want with those things anyway?

“Perhaps I’ll have one of your family,” she suggested impatiently.

“My grandmother, my father, they are old and frail,” I pleaded, wondering what I could offer that would save their lives.

I could count the wolf’s ribs under her patchy fur. Her skin rippled; she was shivering.

“Will you take my coat?”

Surely, my mother would gift warmth to a mother wolf, to trade her dying efforts for protection. What good was warmth without safety? I would endure winter’s bite instead.

I removed my keys from the coat pocket and dropped them into the basket. Shrugging off the coat, I breathed in its scent one more time. It no longer smelled like my mother, my own sweat having seeped into the fabric. I draped it over the wolf’s shoulders, double-knotting the arms across her neck. The coat will soon smell like her.

“It’s very warm,” she sighed with half-closed eyes. The wolf sniffed. Her breath was wet and musty.

Tonight, I will bring a wolf to dinner.

On the way home with the wolf, my eyes did not stray from the path, not even to look for ginseng’s red berries. Without my coat, I was no longer sweating.

When we reached my home, she circled it, sniffing. Could she smell Mu from his last visit?

As Madam Wolf disappeared behind the cottage, I heard someone on the path. My stomach dropped.

I turned. It was Mu. The woodsman carried his ax as easily as if it was a part of his arm. His shirt was sweat stained, covered in splinters. When he smiled, his wrinkles looked like gashes. I wanted to run, to claw his eyes out for even looking at me. Why was he here so early?

As he approached, his shadow engulfed mine, engulfed my body.

“It is so good to see you.” He took my hand from my side and pressed his lips to my knuckles. He had taken on the manners of this new country, where this closeness was expected. “You shouldn’t go into the woods alone. There are wolves in there.”

I pulled my hand back.

“I was safe there.” I did not reach for my keys, refusing him entry.

My eyes traveled up the length of his ax. What if he hurt Madam Wolf?

“My, what a big ax.” I extended a dainty finger to the head of the ax. “May I try to hold it?”

He chuckled. “Of course you may.”

I set down my basket. He placed the ax in my hands and grinned as I feigned weakness. The ax was lighter than the basket I had hauled through the woods. It was lighter than my youngest cousin, who had squirmed the whole night while my aunt searched for her drunk husband.

“It is so heavy.” I gripped it, my knuckles taut.

Mu flexed his arms and shoulders. “They don’t make them for young ladies.”

“My, how sharp this ax is,” I said in a breathless voice that didn’t sound familiar. “How many trees have you cut down?”

“Hundreds!” He swelled, roaring, “Not just trees, but deer and bears.” I imagined the bloody bodies around him, a wasted feast.

He glanced behind him. “I was hoping we could speak before your father came home.”

The hair on the back of my neck rose. I lowered my eyes.

“Why?” I asked through clenched teeth.

“I think we should be married. To make it alright between us. I have already asked your father and he agrees.” He coughed, shrugged. “Well, he agreed yesterday. But today he said I should ask you first. But we agreed you shouldn’t marry a foreigner.”

I gave a derisive laugh at his calling this country’s people foreigners when they used the same words against us. We were all foreigners to the wolves.

“Why not?” My voice dipped lower. “My biao jie may marry that tailor’s son.” Even this country of possibilities could not abide a lone woman.

“They can’t take any more of our women,” Mu spat. Were my cousins like a tea set that belonged together? Did he see me like his ax, his shirt? Heat rose from my chest to my face.

If my uncle had been a foreigner, would my father have defended my aunt? Or was there no other option for a woman and her three children?

“Can you imagine it?” he asked. “You won’t have to wash these foreigners’ clothes anymore. We’ll spend the rest of our lives together.”

The blood rushed in my ears. Every night, his sweat. Every morning, his breath.

No. Not another night, not another morning.

Mu turned at the sound of the leaves rustling behind him. He groped for the ax but I retreated out of reach. I stepped out of his shadow.

He hissed at me, confused, angry. “Give me the ax, you stupid–.”

Madam Wolf landed on him, jaws around his neck. He fell, those large hands stretching toward me. She pinned him to the ground, muzzle darkening with blood. Madam Wolf struck his throat, his shoulders, his hands. Blood pooled under him, soaking into his clothes.

When he stopped moving, she panted. Her warm metallic breath clouded, catching the last rays of sunlight.

She darted back into the safety of the woods.

The front door opened. I spun, hefting the dripping ax.

My grandmother gasped, terror in her wide eyes.

On the bloody ground, there was no other shadow. The widening puddle of blood covered the bloody paw prints.

My grandmother hobbled toward me.

“There was a wolf.” I pointed into the trees. “It had fearsome teeth, and claws sharper than an ax. It attacked Mu.” My voice cracked.

She nodded.

“It stole my coat.”

She laid her tender hands over my splattered knuckles.

“He fought bravely, didn’t he?” she asked as she pried the ax from my hands and laid it by Mu’s body.

I nodded, my hands shaking in hers.

“He saved you from the wolf.”

I shivered, suddenly cold without my coat.

She pulled a handkerchief from her pocket and started to wipe my blood-speckled face. Her voice was steady as she stared into my eyes.

“The wolves here are as dangerous as the tigers back home, aren’t they, granddaughter?”

I nodded, remembering my grandfather’s blood staining the hems of her pants, her hands.

My grandmother repeated the story of Mu’s bravery to my father, to the police. After every retelling, I almost believed her too.

About the Author

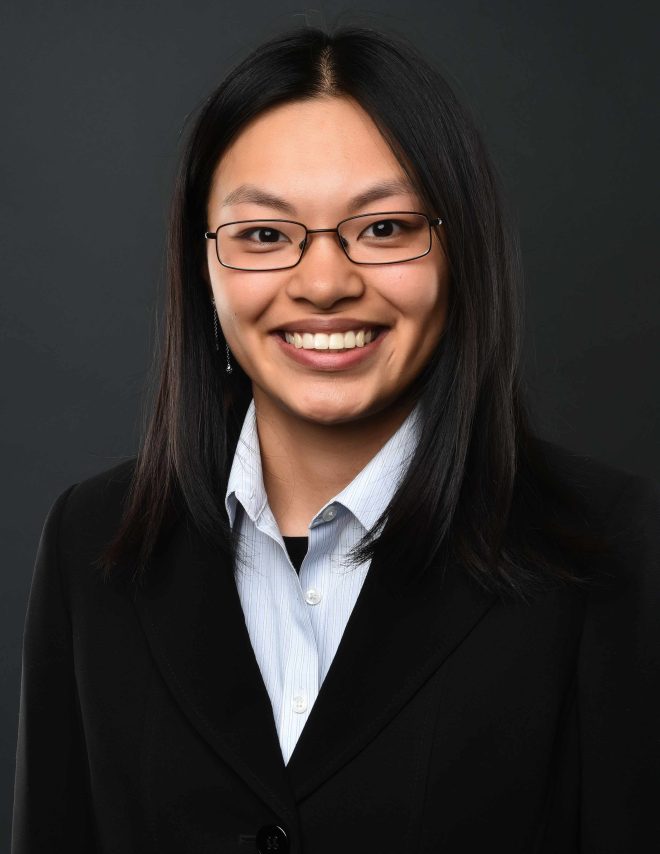

Wen Wen Yang

Wen Wen Yang is a first-generation Chinese American from the Bronx, New York. She graduated from Barnard College of Columbia University with a degree in English and creative writing. You can find her short fiction in Fantasy Magazine, Zooscape, Fit for the Gods and more. An up-to-date bibliography is on WenWenWrites.com. She listens to audiobooks at three times speed, talks almost as fast, and misses dependable public transportation.

About the Narrator

Pine Gonzalez

Pine Gonzalez is a writer and voice actor from the Chicagoland area. They are the creator of the podcasts Tales from the Fringes of Reality and Forged Bonds, both of which also feature their voice. When not writing or working at a bookstore they can be found listening to as many audio dramas as they are able to and playing with their dog Athena.