Cast of Wonders 595: Come in, Children

Come In, Children

by Ai Jiang

Yejin rubbed her eyes. A cyst was growing at the edge of her right lid. She didn’t have to feel this terrible, but ever since she’d stopped draining the youth of lost children who wandered into the forest, the wrinkles had settled in, her brown hair streaked with grey, and her teeth had become brittle, sensitive to brews both too hot and too cold. She hated lukewarm tree sap water, but it would have to do.

When a knock on her door came, Yejin fumbled for her glasses on the nightstand next to her bed. The old crow that lived in the large oak with its branches draped over her mushroom-shaped house hadn’t yet called. It was far too early for the beginning of her business hours.

The rapping against her creaking wooden door quickened—staccato and urgent. But Yejin’s movements remained slow, steady, and calm, as though she were in a trance. At least it wasn’t a smart phone. Technology, she could never understand the appeal. The quietness of the forest was much more desirable than the roar of the city. She refused to use the Internet, though she snuck into the city every decade or so just to peek at the state of the world—more often than not, it was a mistake. People were foolish, brutish, shortsighted, and utterly helpless on their own, but she had renounced the world and did not intend to return, no matter how clearly they required her services. They’d have to come seek her out for it, and there would be a price—there always is.

Yejin slipped her feet into the wool slippers she’d made last winter. It had only been two seasons but they were already scruffy. She loathed having to trudge to the city for more yarn. When she had been young, she had hunted the deer of the forest and made her clothing from their hides. Sometimes she found joy in making the deer forget, pause, so she could pounce while they were confused, but it seemed rather depressing now—a blank stare, a blank mind, confusion before death. Sometimes it wasn’t deer…

The rapping, having paused only for a breath, resumed.

“I’m coming,” Yejin muttered under her breath, knowing her brittle voice wouldn’t carry down the stairs and through the doors anyhow. She’d have to renovate the house to get rid of the stairs soon, at the rate her centuries were catching up to her. It took ages to walk up and down.

Yejin grabbed her cane and took sideways steps down the stairs.

The clacking of her cane echoed in her ear. Instead of opening the door, she first cleared her throat then flipped the sign next to the window, so it showed “Open” in gothic script. Only when the sign stopped clattering against the glass of the window pane did she grasp the bronze door knob, shaped like a shrivelled head, and twisted.

On the other side of the door stood a man in a pressed suit with the tie wind-blown. Sweat had soaked through his white shirt at the armpits, dampening the navy fabric of his suit jacket. His leather dress shoes were speckled with mud and grass.

“You are Yejin?” he asked.

Yejin nodded. “Yes.”

Before the man spoke another word, Yejin waved him inside, leading him to the kitchen without sparing another glance. She settled down only one other chair remained empty across from her. The man took the seat, pulling out an embroidered handkerchief to dab at his neck, his veins bulging beneath glistening sweat.

Yejin wasted no time. “What do you want erased?” She wiped fog from her glasses.

“My father,” he answered, the handkerchief now soiled, clutched between nails that were in desperate need of trimming.

“Not just a single memory? His entire existence in your life?” Yejin’s brow rose.

“Yes. Please.” The desperation in the man’s voice dissipated her hesitance. Memory charms were difficult; and the mind will attempt to hold on to most impactful experiences and recollections with greater urgency. But this one would pay the steep price, and swiftly, by the sound of it.

Yejin hummed then nodded. “There will be a hefty price, do you understand? And you may feel an emptiness where the memory used to be and confusion if you attempt to recollect what was erased. Sometimes you might feel lost and wonder why you desire that which you never had, but the pain will help you grow past it.”

He nodded. “And the payment?”

“Five years of your life. And all memory at the dining table in the middle of the kitchen; of me.” For a being with less power, it would have been a discount price, but Yejin was a refined master of the art of memory manipulation, and she did feel momentary compassion for the sweaty oaf. The second part of the agreement was more of a guarantee that he would not come looking for Yejin again when the side-effects knocked on his door.

His hands clenched into fists cradled in his lap, fingers still fiddling with the handkerchief, fraying its edges. “All right.”

Yejin’s gaze lingered on the man’s balding head before she picked up her cane and headed towards the cupboards.

From the highest cupboard, Yejin removed a jar of aged scrolls, on the verge of moulding. She unscrewed the lid and handed the man inked-marked parchment.

“Take this with you and follow the instructions exactly.” The instructions were from her great-grandmother’s period and Yejin had yet to update them, but it should be simple enough. People never really changed, even as they continued inventing new ways to make loud noises and flashing lights. “Rid your home of all images of your father. Your family and relatives will still remember him unfortunately, so you may need to ensure they don’t mention him around you, or you may get confused and attempt recollection. Perhaps best to avoid them as well.”

The man nodded.

“When you’ve followed all the instructions, return here, and bring the scroll. I’ll take half of the payment now and the other half when the charm is complete,” Yejin said.

The man looked as though he wanted to argue but thought better of it. Yejin placed both of her hands on top of the table, palms facing upwards, and beckoned the man to place his hands in hers. As soon as their flesh connected, she felt energy draining from his body, enter through her fingertips, running through her veins the same time his spasmed, squirmed like worms in boiling water. The man’s head snapped back, gurgling with his mouth stretched wide in a silent wail. His legs trembled, an earthquake shaking through him, yet his feet stayed planted on the floorboards. Yejin cackled, marvelling the whites of the man’s eyes, slivers of red crawling up, up, up, looking as though they may burst. Her customer was suffering, experiencing a taste of momentary death, but Yejin felt alive.

Five years from this worn-out carcass of a man was nothing, like a single sip of cold tea, compared to burning, sweet youth of lost children. But she had sworn off children when her youngest sister left to have her own with a mortal man. Not that Keyi had ever appreciated Yejin’s sacrifices and left Yejin’s heartfelt advice lingering in the air with covered ears. Why did Keyi insist on nurturing a child in her own womb when she could simply keep one of the children who wandered into the woods. Their woods. Now it was only Yejin’s alone. So much power Keyi had given up. Such a pity, the fool. She’d learn the folly of her ways soon enough. To be enticed by a mere mortal man, what was she thinking? She wasn’t, surely. And the live children, one’s own children, those uncontrolled things, they were a headache and a trial at best. Must Keyi be so blind when her elder sister was trying to help her see?

An assertive knock on the door jostled both Yejin and the man from their brief, strange moment of intimacy. The man’s pupils were again in sight, though they lulled side to side, unfocused, eyelids shuddering. With the payment transferred, a few more age lines appeared on the man’s face and a few of Yejin’s receded. The man withdrew his hands, closing his fingers instead around the scroll in front of him. Yejin paused— two customers within a week was nearly a flood, but in a single day? That was unheard of—at least not since the 1800s. And this knock was no timid, hapless seeker of curses or erasures…

“Sister,” came the voice on the other side of the front door.

Yejin’s lips drew in on themselves, forming a thin line. Webbed wrinkles crawled up the sides of her mouth, spreading across the entirety of her face and blending with the purple and green veins beneath the translucent, papery skin of her neck.

Neither Yejin nor the man closed the door, so she could see her sister’s figure lingering by the opening from where she sat in the kitchen.

“Keyi,” Yejin said.

“I told you, it’s Penny,” Keyi said as she pushed inside and past her elder sister. She was still in her thirties—her actual third decade. Draining youth was still an unnecessary thing for Keyi, and she insisted she never would, though Yejin knew her sister would change her mind once the end of her mortal lifespan approached. Keyi would feel far worse than Yejin did now. The centuries between the generations the sisters were born in had caused more of a gap than their mother expected—not that the ancient sorceress had cared much before she perished.

“My apologies, Penny,” Yejin could taste the copper in her mouth. She liked her sister’s birth name better, but there was no sense in starting that argument again.

Yejin stood, leaving the man, who had taken an interest in skimming the instructions. “What brings you here?”

She looked past her sister at the trees that swallowed what would have been a view of the city behind them. The forest would have been swallowed by the expanding edge of civilization, if not for Yejin’s persistent efforts, though that had drastically reduced her number of customers.

Keyi narrowed her eyes and crossed her arms, fingers curling into fists at the end of her elbows. She’d lost weight. “My husband? You took away my husband.”

Yejin cursed under her breath but bent her face into a disarming smile, flashing the gap of her missing front tooth in hopes her sister might realize what she would become by straying away from draining children’s youth. “Would you like to come in and have some tea first? It’ll only be a second. I can get the pot going now.” Yejin took a slight turn towards the kitchen and tapped her cane against the wooden floor.

For a moment, Keyi’s anger seemed to dissipate as her arms fell slack by her side. Her eyes roamed Yejin’s face, no doubt noticing the age. The last time Keyi had seen Yejin was a decade ago when she first left the cottage, their shared home, back when she had first met the man who would become her husband. But back then, Yejin had still looked to be her in early forties; now maybe it was somewhere closer to seventy, or so mortal age went.

There was a squeak as a chair slid back from the kitchen table. “I should—” the man began.

“Yes,” both women replied simultaneously.

“In three days,” Yejin said as the man straightened his tie and rushed to leave.

“Looks like business is still booming, huh?” Keyi sneered, wrinkling her nose as she took the spot the man vacated. Yejin pulled out a rusting kettle and lit a fire under it.

“You’ll feel much better with some proper tea. Better than human food,” Yejin drawled, despite the lingering flavour of sap on her lips.

“That’s only because you haven’t tasted the restaurants in the city yet.” Keyi rolled her eyes.

“No need.”

There was a brief silence.

“My husband,” Keyi repeated the words she said when she first entered the house, scraping her nails against the chipped oak table. The wood flakes loosened and embedded themselves into Keyi’s finger, but she took no notice. “You erased him.”

“Yes, but you requested it. Don’t you remember?” Yejin kept her expression neutral, but her heart pounded within her. Would her sister catch the blatant lie? “You’d said you’d finally grew tired of him. He wasn’t so great after all. It’s just as I have always said—”

Keyi laughed, high-pitched and slightly deranged. She tossed her head back, arching her spine, resembling the man earlier.

“I requested it? We both know that’s impossible. You wanted it.” Keyi’s expression darkened as she looked at Yejin, baring her teeth. Yejin had once thought her sister would grow out of her chaotic teenage years, but the wildness within her, though tempered by age, sometimes slipped momentarily, causing dark episodes.

Yejin abandoned her lie. “You belong here, with me.” The kettle screeched as the water came to a boil. The scent of metal and steam filled the air, almost like sizzling blood.

“Why did all our other sisters leave then?” Keyi prodded.

Yejin did not reply as she put out the flame beneath the kettle. She settled back in the seat across from her sister after filling two deer skull mugs with steaming oak root tea. She slid the cracked one across the table, keeping the good one for herself.

“I just want to be happy, Yejin. Not that you ever knew, or will know, what that means.” Keyi spat in the tea then left it untouched, glaring in disgust at the whittled skull by her hands. “Where did you hide his photos?”

“How did you remember him?” Yejin asked, knuckles turning white as she gripped her mug, the heat singeing her skin.

Keyi pulled out a phone—the lock screen displayed an image of her and her husband armin-arm. “Just because you broke the old one, doesn’t mean all the data is lost. But you wouldn’t know that having been out here for so long.”

“So you’re back together, then?” Yejin asked, attempting to be nonchalant.

Keyi’s face twisted, and she turned to the side. “He’s dead.”

Yejin’s nail dug into her mug until a crack appeared, until it grew, steaming liquid leaked onto the table, through its crevices, cooking her flesh. She raised the mug, allowing the tea to roll down her arms, leaving angry red welts. Behind the skull, she tried to conceal her grin.

“How?” she asked, standing up.

“I didn’t recognize him when he into the house so I hit him over the head. A little too hard, it seems.”

Keyi seemed too calm, but Yejin only thought of how to keep her sister from imprisonment.

“Perfect! You can hide here,” Yejin said, but Keyi shook her head.

“I need to get rid of the body first, and I’ll need your help.”

Yejin’s blood chilled at the thought of going into the city. All the vehicles and the unnatural sounds. But her sister, she had to help her sister. Keyi finally understood where she belonged. She was coming home. Yejin found herself nodding.

Yejin failed to notice the clear exterior differences between her and Keyi until they stood at the edge of the forest: where Keyi donned a peach cashmere sweater and jeans, Yejin wore a long plain grey dress with a brown cloak drawn overtop. Yejin looked over her shoulder but could not catch a glimpse of her home—the shrivelled mushroom top on the verge of collapse but never actually collapsing, the withered flowers that were very much living, and the gates made up of the skulls of both humans and animals. The city was full of life. Death comforted her.

By the road that passed closest to the edge of the forest, Keyi had parked her small blue car. Yejin eyed it with caution as her sister hopped into the front.

“Would you rather walk instead?” Keyi huffed in impatience.

“I could conjure us the legs of the crow for the stretch of our journey?”

Keyi frowned. “We’re not doing that.”

A low grumble left Yejin’s lips as she climbed into the passenger side. She shuddered along with the engine as it started.

Before they arrived at Keyi’s house—only half an hour away—Yejin had thrown up a handful of times. Sometimes on the side of the road if Keyi pulled over in time, but more often it was on Yejin’s wool shoes. By the time they reached Keyi’s condo, the entire car smelt of oak root tea.

Yejin covered her ears as they headed into the condo. The sound of a train running against its tracks boomed far too close to where the sisters stood. A car rolled past the front of the building, blaring its horn for what felt like the entirety of the middle ages. In the visitor’s parking lot, a car alarm went off. Even the sound of chirping birds along the humming power lines annoyed Yejin—a sound that would usually be calming in the forest.

It was noisier than Yejin remembered it being when she had snuck into Keyi’s apartment the first time to get rid of traces of her husband. It had been a futile attempt, but she had to try anyhow. Her sister felt more distant with each passing year, and she hadn’t realized the disillusionment of humanity quick enough for Yejin’s liking. Yejin was growing tired of feeding on the stale years of overstressed and anxious businessmen and women, young adults going through an existential crisis, and avoiding the lost children who still stumbled upon her house every year. She needed a proper meal, but she couldn’t risk harming one of her own nieces or nephews, assuming Keyi produced one or several.

When Keyi opened the front door, Yejin spotted a puddle of blood that looked too bright, soaked into an off-white faux fur carpet. In the middle of the pool sat a small wind-up duck, blood splattered around it. From the corner of her eye, Yejin noticed a shadow darting towards her. It wasn’t until her hands were bound behind her, when her cane had clattered onto the floor, that she realized it was Keyi’s husband Hunner—alive.

“Goodbye, sister,” Keyi smiled and clenched Yejin’s hand in her own, causing a protesting screech to escape her elder sister’s throat.

“Keyi!—”

“My name,” she said, “is Penny.”

Keyi’s nails, like a crow’s claws, drew blood from Yejin’s wrinkle webbed palms. Yejin eyes rolled back, back arched, and convulsed against the cage Hunner created around her with his arms.

Yejin’s eyes refocused. There was oak root tea in a deer skull mug on her nightstand. She didn’t remember brewing it. She took a sip. It was cold. A small cloud of strange froth floated on the golden brown liquid’s surface. The tea leaves at the bottom stirred, fluttering, as she placed the mug down.

There was a knock on the door.

Yejin moved to stand, wondering who it could be when her business hours hadn’t yet begun. But she noticed an odd glow outside the window: the sun was setting rather than rising. A panic rose within her as she took unsteady steps, her joints feeling stiffer than they had the day before. She stumbled forth, swaying. A jolt shot through her hips. Her eyes widened at her aged hands—ancient compared to the youth she remembered she had from what felt like only minutes before. Never had her lips felt so dried, cracked. A burning thirst ravaged her from within. How long had it been since she tasted the rejuvenating taste of youth?

What had happened the day before? There was a man—the one who wanted to forget this father. But that couldn’t possibly be all she had done that day?

“Excuse me!” came the voice of a woman.

Yejin hobbled towards the door.

The “Closed” sign was already flipped to “Open”.

“Yes, yes—”

She stared as though someone might materialize if she looked hard enough, but no one was there. On the door mat outside the entrance lay a rolled up scroll. But unlike her moulding parchments, the material of this paper was bone white, except for where it met the dirt that had collected on the mat. There were no instructions within, only a small completion symbol sat in its center.

Who did it belong to? Perhaps one of her sisters who might have passed through? No matter. She was far too tired to deal with this. It was intolerable, being weak and elderly.

Her fingers brushed across the smooth, unnatural surface of the parchment. It was better to burn it than to leave it laying around. If another sorceress tempered with it, who knew what chaos they’d brew up.

Yejin shuffled toward the kitchen after taking one last look around her home, narrowing her eyes at the trees. After starting a fire for her dreadful sap tea, she fed the flames with the scroll, watching the white sheet curl and turn into ashes beneath her kettle. The fog she woke up with earlier began to settle as the remainder of the scroll left her finger tips.

When the kettle screamed for attention, there was another knock on her door. The man.

Yejin sighed. Why was everyone be so keen to forget those bound to them by blood?

Yejin flipped the “Open” sign so it showed “Closed” and waited until the clattering of the wooden sign against the glass stopped before she left the window side.

“Mama?”

Outside, a young child wandered in the forest—lost. A lucky day for Yejin. She prodded her legs with her cane. How long had it been since the last child? She furrowed her brow. Why had she stopped?

Yejin made her way out of her cottage as the child neared her gates, seeming unfazed by the skull and bones that made up its entirety.

“Mama?” the child asked, frowning. “Who are you?”

The child had a face like someone Yejin should know but could not remember. But maybe if she kept the child, just for a while, and stared hard enough, she would recall the person she had forgotten.

She had told someone it was all right to take these lost children into her home for as long as they wished, hadn’t she?

The fog rose again like a veil in her mind. It required energy Yejin didn’t have to draw back its curtain. Perhaps she would have the power after she was done with the child… She nodded, refocusing on the child who stood with sharp clarity in front of her—an entity of endless youth.

Yejin smiled, feeling wind chill the flesh around the gap between two teeth. When did that appear? It would be gone soon, anyhow. “It’s quite cold outside. Would you like to come in and have some tea first? It’ll only be a second, and then we could go search for your Mama together.”

Surely the child wouldn’t catch her blatant lie, would she?

About the Author

Ai Jiang

Ai Jiang is a Chinese-Canadian writer, Ignyte Award winner, Hugo, Astounding, Nebula, Locus, Bram Stoker, and BFSA Award finalist, and an immigrant from Fujian currently residing in Toronto, Ontario. Her work can be found in F&SF, The Dark, Uncanny, among others. She is the recipient of Odyssey Workshop’s 2022 Fresh Voices Scholarship and the author of Linghun and I AM AI. Find her on X (@AiJiang_), Insta (@ai.jian.g), and online (http://aijiang.ca).

About the Narrator

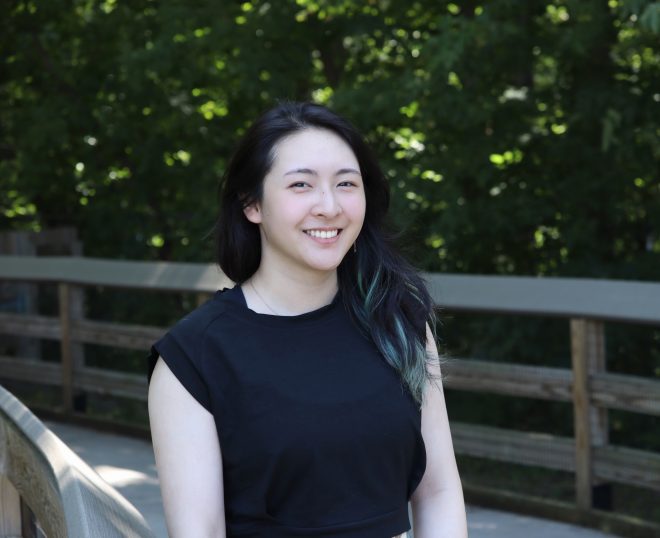

Melissa Ren

Melissa Ren is a Chinese-Canadian writer whose narratives tend to explore the intersection between belonging and becoming. She is a prize recipient of Room Magazine’s Fiction Contest, a grant recipient of the Canada Council for the Arts, and an editor at Augur Magazine and Tales & Feathers. Her writing has appeared or forthcoming in Factor Four Magazine, Fusion Fragment, DreamForge Magazine, and elsewhere. Find her at linktr.ee/MelissaRen or follow @melisfluous on socials.