Cast of Wonders 582: Open Skies and Hellfire

Open Skies and Hellfire

by Olivia B. Chan

I liked to think of myself as a morally sound individual. It was easier to do when I wasn’t smuggling gunpowder to a teenager who may or may not have planned to blow up the caverns with it.

The smudgy teenager asked, “How much?”

I said, “An unreasonable amount. What are you going to do with all this, anyway?”

Caver kids had a certain look, and this one exemplified it. In the dark of the cramped tunnel, our two lanterns converging to cast multifaceted shadows, her skin clung to her bones. “How much do I pay?”

I smacked the side of the crate I was leaning against. The trolley I’d “borrowed” to transport the gunpowder rattled. “Five vials of dust for one barrel.”

“Five vials.”

“That’s what I said, yeah.”

She bit her lip. I was likely going to have to give her the trolley, too—no way she could carry the crate with those knobbly arms.

“Six vials for the trolley and the barrel,” I amended.

“Five.”

“Seven, if you keep stalling.”

She sniffed, then rustled through her knapsack. Its flap knocked against her hand while she searched, and she kept pushing it away, brow furrowing more and more.

As I watched her, I decided I didn’t need to be too awful. “Five vials, if you tell me what in the hells you’re going to do with all this powder. You can’t be gunning for a raise.”

If there was one thing you could rely on in these miserable caverns, it was what you would see in the eyes of caver kids. Always, they were brown without remorse, with no sunlight to illuminate scraps of silver or gold or hope. No apologies. No regrets. Which was for the best, since they couldn’t afford regrets: the average caver kid died before their seventeenth birthday, killed by a collapse or a misplaced explosive. This one looked around fifteen. That gave her two more years of unearthing the Bones—she didn’t have a hope of seeing the work completed.

“I’m going to make a bomb,” she said, and held out five vials of dust.

I turned the plastic tubes over in my hands, popped the lid off of one. I held it up to my lantern. “Yeah, I can tell. What’re you going to do with a bomb?” The dust checked out, faintly green and terribly nauseating. I slipped the vials into my satchel, then looked back at her.

She glanced away. Her lantern shifted, throwing light blurred by fingerprint-speckled glass over rubble and rocks.

“I mean, do you know how to make a bomb?”

“Thank you for the gunpowder,” she said. “You can leave now.”

She wasn’t even going to make sure the barrel was full, was she. “Kid, I can’t leave you with this stuff if you don’t know how to use it safely. It’s part of the runner code.”

“That’s not true.”

“I’ve got rules to follow, kid.”

“Stop calling me kid.”

“Fine, fine. What’s your name?”

“Sun.”

“Okay, kid, I’ll cut you a deal—let me teach you how to make a bomb without accidentally eviscerating yourself, and then I’ll leave. You get safety and, I don’t know, prosperity, and I get to follow the very strict runner code so I don’t get fired.” You’re a fool. You’re such a damn fool, Lielle.

Sun frowned. “I have to get back soon.”

I asked, “If we make this bomb right, will there be a tunnel to get back to?”

She looked at me as if to say, Don’t be obtuse.

“The first step of making a bomb is getting to the surface,” I said.

I was lying through my teeth.

Runners didn’t have a code; runners didn’t have anything except luck and good looks. But I knew cavers like Sun, cavers who’d seen more mangled bodies than years alive and breathed in too much dust to be entirely mortal. When the Bones were fully excavated and the Serpent woke to slither out of dirt and into the sky, they knew they wouldn’t be watching. Sun wasn’t building a bomb for extra cash, or to impress her superiors with a skillful excavation. Sun was building a bomb for chaos, and collapse, and probably revenge. I knew the stories: a caver got a limb torn off in a preventable accident, or watched a loved one die—same thing—and then the next day their portion of the cave was blown to smithereens. If they were lucky, an important route was blasted to bits and the higher-ups had to take notice. If they weren’t, and no one could call cavers lucky, the groundspeople considered it a section excavated with remarkable efficiency, no matter who was hurt. In short—thank the hells I was fast enough to be a runner, not a caver.

Sun was not fast.

As we began our third break, she said, “You don’t have to be here if you don’t want to be.”

I took my water flask back from her and poured my anxiety into twisting the cap as tight as it could go. “Listen, I don’t want to be here, but I have to be, because of the code. We need to hurry this up. I have another job soon, an actually legal job, and if I’m late, well, no one else is getting any gunpowder.”

“Then leave,” she said. Like it was the most obvious thing in the cave. Like she was pointing out a climbing route.

I said, “I’m not going to leave. We just have to move a little faster, because—”

“I can’t move faster.”

“Sure you can. We haven’t even started running. We have more than enough water, and I’ve made this trip in an hour flat before—”

“Why won’t you leave me alone? You’re a runner. You don’t care.”

“Don’t be so prejudiced.” I gave a small smile, but she didn’t.

“You don’t care,” she repeated. “You don’t know me.”

What was I supposed to say to that? Again, I asked, “Why do you want to make a bomb?”

She grabbed the handle of the trolley. “I’m going back by myself. Thank you for your business. Goodbye.”

The trolley squealed as she tugged it in short bursts. The grating noise echoed down the tunnel. It took her five tugs to leave the halo of my lantern, and she didn’t look at me for any of them, choppy hair and split ends falling into her eyes. At least she was committed.

“My name’s Lielle,” I said, “and I do know you.”

The next tug made her lantern thump against her forearm, skin dangerously close to flame.

Figuring no one else would ever hear this, I said, “I know you don’t know how to make a bomb, and that you have the materials you need despite that, nicked from the adults while you were supposed to be sleeping. I know you don’t want to make a bomb but you feel you have to, that it’s owed. I know you have friends, and those friends would bring down the cave for you, too, and I know you don’t give a shit about the Bones. I wasn’t always a runner. No one’s born a runner; you should know that. And if you aren’t a runner or a groundsperson, you’re a caver.”

In response to this baring of my heart, Sun said, “Lielle is an awful name.”

“Oh, shut up. It’s not like I had a lot of options.”

When she turned back to me, she seemed hopelessly small, a matchstick. Ready to ignite or snap. I wondered what made her need to build a bomb—who made her need to build a bomb, who collapsed the sky by not waking up. Or by waking up mismatched. Given enough time, exposure to the trace amounts of dust present in the excavation tunnels could drive people mad. Though if that was the case, it could have just been prolonged exposure to Sun, not dust-madness.

“Do you think you can make the Jaw?” I asked.

She nodded, and I waved her closer. If we were going to put this gunpowder to use, we needed to begin before we reached the surface.

The Jaw didn’t look dangerous. The final stretch before the mouth of the cave was flat, solid stone, lacking the typical trappings of treacherous fissures. Enough light from the opening got through for me to blow out the flame of my lantern. I glanced at Sun, who was taking it in with a scrutinizing scowl.

The first time I sprinted down the Jaw, I was running away. I hadn’t expected to make it to the surface: without a map, the tunnels were a death trap. Though it was cold, I had been warm, my feet blistered as the moon, my mouth starchy with the aftertaste of stale water. I hadn’t known how the Jaw worked—it was raw luck of the desperate, bloody kind that got me through. I saw the opening, the light, and I thought I was free. I knew I was abandoning my sister and I didn’t care. Over the years, I gathered a hundred justifications: she was loopy on dust; she genuinely cared about the Bones and wanted to see the Serpent, alive, in the sky; she wasn’t fast enough.

None of those reasons mattered, only that when I reached the surface, the groundspeople sent me back with arms full of supplies. And when I returned, now named Lielle in runner tradition, she was gone.

Sun said, “It doesn’t look that bad.”

“And you don’t look annoying. Appearances can be deceiving.”

The Jaw was treacherous because it was the skull of the Bones, the first place excavated back when the right materials weren’t available. As such, it was rubbish with dust—the volatile stuff, completely different from the stable types in the deeper tunnels. It was settled now, but the moment we stepped on it, it would explode into an all-consuming cloud, like the bastard son of a tornado and a drought. In excess amounts, the dust flaking off the Bones was a killer.

“You look exactly how you are,” Sun said. “Raggedy and dirty.”

“You are so polite. My regards to whoever raised you.”

She exhaled, and the hair over her face fluttered. She nodded.

“Ready?” I asked, setting my extinguished lantern onto the crate, next to Sun’s. I could come back for the trolley and the barrel later. Everything we needed was in her bag.

“Ready,” she said.

For a split second, her shaky breathing was the only thing filling the space between us. Then we ran, and that changed.

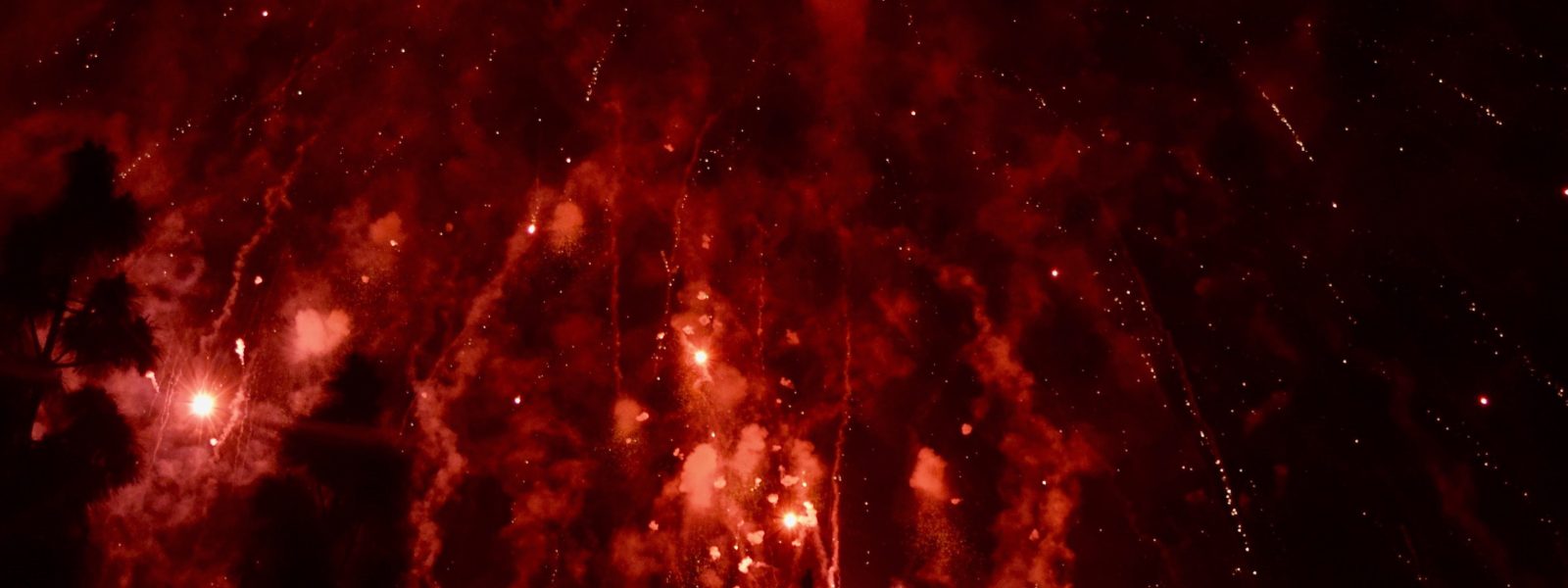

The dust flared up all at once, in hues of green and blue and yellow. Crisp grass and amber sunrises. Open skies and the hellfire within the Bones. It was beautiful, it was brilliant, and it burned. My skin was kindling. My lungs were ashes. A little farther. Only a little farther.

Sun stumbled. I seized her arm and dragged her to the end of the tunnel, where we collapsed on red dirt.

After hours in the caverns, fresh air was like a scream cutting off into silence for me.

After years in the caverns, Sun gasped, and she laughed. She laughed and she laughed and she laughed, rolling over in the dirt to sit up. Her face was plastered with the colours of the Jaw—us runners called it airshock, as though it was from the joy of emergence rather than the dust. With her clothes soiled by red dirt, Sun embodied the whole world, the smudge of blue on her face the sky, the maroon on her collar the horizon. She was each of the postcards passed around the runner quarters, a sunset that really wished you were here.

Beyond our smear of rubble and dirt, green plains stretched to the horizon, broken up by a couple of the groundspeople’s houses. Sun’s disappearance hadn’t been reported; there was no one waiting for her.

She said, “I am never going back down there.”

I smiled, not unsympathetically. “Good luck with that, kid. You got the bombs?”

“What’s so outrageous about not going back?”

I didn’t miss her avoidance of the bomb question. “There’s nowhere else to find work, not yet. Trust me, I’ve tried.”

She laid back down and watched the clouds drift by, and even though we were wasting time, I let it slide. Just this once.

We moved at nightfall. The excavation caves were set into the side of a hill. While making the explosives, Sun had decided she wanted to plant them on the hilltop. I didn’t protest, as much as I wanted to. This was hers.

Despite her speed in the Jaw, Sun took her time hiking up, pausing to take in the stars, to drown in them. She took off her miserable excuses for shoes and walked through the rocky terrain barefoot.

Eras ago, the Serpent had been imprisoned here, trapped beneath stone. Someday, the excavation of the Bones would be complete, and that beast would spread its wings once more, skeletal and holy. Tonight, though, there was only me and Sun and our gunpowder bundles, carefully rolled and packaged the way I’d shown her.

Sun clawed a small hole into the ground and placed the bundles within, fuses up. I handed her a match from my satchel. She asked, “Is this right?”

I didn’t know how to answer, and I didn’t have time to figure it out before she lit the fuses and ran back.

If they were bombs, the hill would have caved in. The delicate lattice of tunnels beneath us would have been crushed completely, killing everyone. Sun would never have had to return, but the cost …

They were not bombs.

The firecrackers crackled to life, spinning, weaving a halo of light.

Their light, ripping through the dark, was the only pure bullet wound I’d ever seen. The dust I’d slipped in blazed fiery blue.

Sun whipped toward me, mouth agape.

I knew what I should have said, what I’d planned to say: You can’t destroy them by destroying yourself. You can’t hurt them by hurting people they don’t care about. The world doesn’t end and begin with the cave, Sun, and when I said not yet I meant that we are trying for change. I meant that we are fighting for it, and we can mean you if you want it to.

Instead, I said: “You can be angry, but I’m not going to be sorry.”

She only looked at me, those caver eyes reflecting the stars, anything but empty.

Forget the Bones. She and the other cavers were what would reawaken the world. And that began with me hugging her tight, promising nothing but no apologies.

About the Author

Olivia B. Chan

Olivia B. Chan is a high school student who lives in Canada with her family and a terrifying amount of notebooks. She spends her free time searching for rabbit holes to tumble down and portals to disappear into.

About the Narrator

Justine Eyre

Classically trained actress Justine Eyre is an Audie Award-winning narrator with over 700 audiobook titles to her name. She has lived in far-flung corners of the world, from Canada to the Philippines, Germany, France and England – her international upbringing and multi-cultural family allow her to come by accents authentically. Justine has appeared in a number of TV series such as Mad Men and Las Vegas, including a memorable turn on Two and a Half Men as love interest Gabrielle.