Cast of Wonders 578: Cold Blessing

Cold Blessing

by Kelsey Hutton

The wind had gnawed his skin raw by the time they reached the nun’s door, the damp air sunk deep into his bones.

A warm orange glow leaked out of the small cottage into the night. While his daughter bounced about in front of him, immune to winter’s bite, he spread his hand out on the door. There, briefly. Not warmth, but a respite from the cold.

Then he shook himself straight and crushed the ice out of his moustache. He wasn’t here for respite. He was here so he would never need respite again.

He pulled Maisy in front so she could dart through the door as soon as the nun opened it. “Ready, girl?” he said. “Be good now, hear?”

The child was babbling to herself. She didn’t even look at him. Instead she careened a whitish lump about in the air. It was a bit of china clay, covered in silt, that had left streaks all over her hands — and, now that he looked closer, the sleeves of her best dress. And after he’d specifically made the wife wash her up!

“Creep, creep, creep,” she chirped and tried to march the clay over his coat cuff.

“Maisy, enough!” He jerked his arm back before it could leave marks on his Sunday suit. He tried to grab it out of her hand, but she twisted away. Her toady eyes bulged further as she laughed.

He unclenched his jaw with some effort. Very well. Let her keep her muck, along with that nose and those teeth and that hair. The fact of the matter was, washing wasn’t the problem. His only child would be plain no matter how coarse the brush.

“There’d better be hope for you,” he muttered and rapped the door three times. Behind him, the sea roared.

No one denied the nun was an odd one. She wore the robes of a nun, but not the wimple. She never bothered anyone, but the sexton refused to call her Sister. She even had the occasional sweet for a village child.

But most importantly, she had the touch.

The nun edged opened the door. As if on cue, a fierce gale tackled father and daughter from behind. He braced one boot inside the warped doorway as if for balance. “Sorry — so sorry, Sister, to barge right in — Maisy,” he hissed, “g’on,” and the girl shimmied obediently. The nun gaped, but moved quickly into the gap to block the child from wriggling in.

“Was I not clear?” the nun snapped. “I said no!”

He’d never been this close to her. When she’d refused him twice before, he’d thought her stubborn even for an old nag. But now, up close, she wasn’t as worn as he’d remembered: indeed, her black eyes were large and comely, if spaced strangely far apart.

“Hullo!” the child said with a broad smile. He tried to press her forward, but her shoulders were well wedged between the door and its frame. She wiggled one arm free and waved at the nun’s face as vigorously as if she’d been across the Thames rather than squished against her skirts. “May we come in, please?”

Briefly, when she looked at Maisy, he thought he saw the nun flinch.

“Please, Sister,” he said. “Twilight is long gone. Exposed like this, at night … if nothing else, we must get out of this blistering wind. It is too bitter to turn around now, not without a temporary relief.” He saw her hesitate. “Look at the child’s fingers! Bone white with cold!” Or clay. “They’ll never survive the walk back.”

Without quite meaning to, real desperation crept in. He thought of the wife, their plain cottage, their mean little meals. He thought of her fingers, bleeding from twisting dried kelp into logs for the fire. His own were barely sensible anymore, after so many years hauling fish through icy water. Worst of all was that there was no end. Another winter. Another catch. Another night steeped in the stench of fish. “Is this what you want for your only child?” he had demanded of his wife that night, when she wept and begged him not to go. “Don’t you want better for her?”

“You’re a fool,” the nun said finally, but she moved half a step back.

Inside, heady heat seeped into his aching knees. There were a few candles and a kerosene lamp set on a rough-hewn table, offering what light they could. Women’s cooking instruments hung from the ceiling, though he couldn’t be pressed to name them. Across the back, a long sheet had been strung up with twine, cutting part of the room off from view. The whole cottage smelled thickly of something sweet. Honeysuckle, perhaps. The nun did not latch the door behind them.

“I brought you a present,” the child announced, to his surprise as well as the nun’s. She held out the pebbly lump of clay. “It’s a mouse!”

“Maisy, no — ” he started, but the nun held out her hand. Long white fingers wrapped around the gift.

She looked just like the wife when she’d swallowed a fishbone.

“Papa wants you to bless me so someone rich will marry me,” the child announced, “even though I’m not pretty like other girls.” Then she promptly lost interest.

The nun drew a sharp breath and stepped back.

“Well,” the man fumbled, cursing the girl’s long ears, “or something that would do her good a bit sooner … a long-lost rich uncle, perhaps?”

The nun’s expression, if possible, got harder still.

The moment of goodwill was gone. “Get out, both of you!” She nearly shouted.

“The child puts it so bluntly — ” he tried. The nun hooked Maisy by the arm.

“No!” She started pushing them out.

“A bit of kindness — ”

“Go!”

“Please — ”

“I don’t bless children like her.” The nun shoved Maisy past the doorstep into the cold.

“Now wait just a minute, there!” He bristled and planted his feet.

“When you first moved to this village, Sister, we welcomed you, despite not knowing where you come from. We knew your sacred profession, and we saw your kindness for the village children, even the cruel or priggish ones.” Bewilderment was creeping into his voice, he could hear. He drew a deep breath to wash it out. “We know you don’t like being asked to perform rites, but I seen the change in those children after they come to your attention. You bless them! It’s true!”

Two bright red spots appeared in her white cheeks, but he hurried on. “You bless them, and afterwards they marry rich, or get bursaries to fine schools, or … or the like. And, I know” — here he drew himself up to his full height — “I know I’m only a fisherman, but I am a father. As a father, it’s my responsibility to make sure my child’s prospects, no matter how dim, are well cared for.”

He could see it in her eyes, the already-begun shake of her head. She was going to refuse him again. Their life would continue, small, meager, and hard, like the potatoes they boiled endlessly for tea. “Please, Sister!” he cried. “Try to imagine what it’s like, having a child you’d do anything for,” he begged. He could well imagine shivering in their damp little cottage all the rest of their days. “Please!”

The nun’s mouth twisted into a crooked pink wedge like the snails he used for bait. All three of them, even Maisy, stood frozen in place.

A gale shrieked past them through the little hut’s open door. The candlelight wobbled drunkenly, and shadows leapt at each other’s throats. For the first time, the fisherman noticed another smell underneath the sweet honeysuckle. His eyes stung with its vinegar sharpness and he blinked repeatedly, wondering how he could have missed it before.

A chill crept up the soft undersides of his arms.

Her shoulders clenched tight, but still the nun wouldn’t speak. Then she broke her stare and glanced, quickly, furtively, to the curtained end of her cottage. Only one glance. It was enough.

She pulled them inside, then choked off the wind with a slam of the door.

The nun leaned her face down to the child’s. “Maisy, right?” she asked, all trace of her anger washed away. Her smile nearly made her beautiful, and the fisherman’s blood suddenly quickened in a way shameful to a man with a wife.

Maisy nodded back with a smile full of crooked teeth.

The nun gently put the gift of clay on the table. He was surprised she’d held onto it this whole time. The nun led the girl towards the back, where a small noise rustled.

“Tell me, child,” the nun asked gently. “I am sure your father and mother have taught you to be a good Christian, as parents ought. But do you ever fail in your resolve? Act unkindly towards others?”

“Sometimes,” the girl answered.

The nun wrapped her long white fingers around Maisy’s arm. “And — ” the woman’s voice croaked. “How do you make up for it?”

They were at the grimy edge of the curtain now. The woman’s eyes never left Maisy’s face as she reached behind her. The fisherman, still by the door, shifted on his feet. He better not lose his toes to frostbite on the long walk home.

“Mama makes me do penance,” the girl said and touched the nun’s cross, swinging gently at eye level.

“Penance …” The nun released her breath in a whoosh. “Yes, that’s the word.” Then she swept back the cloth and the wave of stench hit him like a fist.

He gagged, woozy, but not before he saw what the sheet was hiding, it, a body, a child’s body. It lay on a bed of slithery fronds, a little boy’s body but with wet hair and skin the white-green of a mackerel’s belly. And its eyes — the lids — the fisherman looked harder, damning himself as he did — they were shredded as if nibbled by crabs. Only a few tufts of eyelashes were left, and gleaming, pale, under the lids — eyeballs like jelly.

“Maisy!” he called and gagged again with the stench. The girl had buried her face in her hands; to hide from the smell or the sight, he didn’t know. Then cold hit his lungs so hard they seized. He clutched his chest. The candlelight flickered wildly, and he could only catch glimpses of his daughter through shifting shadows. Maisy, no longer docile, was yanking away from the nun, her one arm reeling out like a line, almost popping from her shoulder while the nun, that witch, wrestled to keep hold of her hands.

“I would never have chosen a child as sweet as this!” the woman whispered, with a turn in her voice almost pleading, with those eyes so large, like a beetle’s. Like a demon’s. “But you would not let it go, would you?” She now yelled at the man. “As if you know what makes right wrong and wrong right. As if you know what a parent would do for their child!” And she joined the dead child’s hand to Maisy’s.

Maisy dropped to her knees. The boy didn’t stir. The man broke through whatever had kept a deathly grip on him and ran to his only daughter, but the woman elbowed him in the gut with more force than she had a right to. He dropped to his knees.

Maisy’s eyes were as round and unblinking as a pickerel’s. She grew still, more still than he’d ever seen her. Steam rose off the children’s clasped hands. Maisy’s cheek sallowed, and the boy’s — the thing’s — pinked.

The fisherman couldn’t move or breathe. He could only hear his wife’s voice in his head. “Don’t take her, husband — that woman! The things she does!” She’d warned him, more, begged —

“What are you doing, witch?” he finally gasped. “What kind of blessing is this?”

“This isn’t the blessing,” the woman bit out. “This — ”

He shoved past her, but just as he reached for Maisy the nun grabbed his fingers and twisted them back with that demon strength. He gasped and froze, and she caught him like that, her grip tight, his joints screaming, their hands in mid-air beside the children’s.

Her face moved right up to his. Her words tumbled over each other like spume. “I could take it back,” she gasped. He started to agree, but she cut him off. “But my son! The sea swallowed him, ripped him out of my hands, after we’d run away so they wouldn’t rip us apart, after we thought we were safe. The waves spat him back out, almost the same, almost, but he was so cold.”

“This is your child?” the man bleated. A nun, with a swollen belly. Spreading her legs for someone other than God.

Her lips twisted again, and her beetle eyes narrowed. “Yes,” she hissed. “I can see you judging me already. But I tried.” Her voice rose to a panicked pitch. “I tried to treat with the Lord! I did! But the Lord wouldn’t listen. I had to make a deal with someone … else.” She shook his arm, and a sheen of tears fevered her eyes. “My boy was so cold. How could I leave him like that?”

He couldn’t rip his eyes away from hers. “Now I keep him warm, for a while at a time, until one day, He” — she broke eye contact only long enough to look at the floor, through the floor — “will bring my boy back to me.”

The fisherman shook his head, back and forth, eyes tearing, unable to blink.

“It’s only a little warmth from the girl,” the woman insisted. “She’ll live on normally, most of the time. And I can bless her. I have the touch. This isn’t the blessing, don’t you see, but after … I can make her life easier. Make your life easier. That at least. Is that so wrong?”

The vision engulfed him. The three of them in a London house far from the stink of fish. His moustache silvered, but full. The wife was smiling in a rich red dress with pearl beading, looking almost like when she was young. Maisy, grown-up now, sat the closest to the fire and nodded to no one in particular. She was wrapped in shawls. A footman interrupted gently to bring them tea. Cranberry scones, and not a potato in sight.

Loosened pressure around his fingers brought him back, and he yelped at the sudden lack of pain. “Should I still bless her?” The nun, witch, demon, he didn’t know, now stroked his trembling fingers. “Should I bless her?” she pressed, but softly, her voice like velvet. “Or should I take everything back?”

It wasn’t Maisy’s life. The witch wasn’t looking to take her life. Only a little heat.

Suddenly he could blink again. He closed his watering eyes and nodded, sharply, once. “Do it,” he whispered.

All four of them fell back, released. He caught Maisy and finally pulled her away from the corpse. She shook once violently, then in small tremors. Her eyes wouldn’t focus. “Cold, Papa,” she whispered. “I’m cold.”

The witch stroked the dead thing’s rosy cheek. He never opened those jellied eyes, thank God. The fisherman touched Maisy’s skin. It was ice.

He took her tiny hands, fingernails purple, and rubbed them between his own large palms. The woman got up and reached for something in the cupboard.

He had to try three times before he could get the words out. “How long does it last?”

The woman spat out a “Huh!” She was back with a bowl. She dipped her fingers, mumbled some words, and sprinkled water on Maisy’s hair. He thought it holy water until he smelled the brine.

Maisy’s hands wouldn’t warm up. My God, he thought. My God.

The woman finally looked at him again. “I do my penance,” the creature said instead of an answer. “She will marry a banker, one so rich he twists dollar bills to light his cigars.” She sat back on the bed of fronds, beside her boy, and turned her back to the man and his daughter.

Maisy trembled and looked past him with drained eyes. He remembered the other blessed children, the cruel ones. With the luckiest of fortunes … and dull eyes, and clammy skin.

He choked as he picked up Maisy. He remembered the lump of clay and swiped it from the table. “Play with this, child.” He pressed it repeatedly into her hand, but it only fell from her numb fingers.

The fisherman held his daughter in his arms, chin tucked in, and turned to go. “I wouldn’t have taken from her,” the nun said suddenly. “I tried so many times to resist.”

He spat in the direction of the fallen nun. “Spare me your piety,” he managed.

She turned her head slowly, then rose, and he swallowed this one act of defiance like bile. “You still judge,” she said. “Even though you know now how easy it is to make one decision, then another, then another, and suddenly you’re making a terrible choice you never thought you’d make.” She was in front of him now, leaning in close, so close his stomach curdled. “But remember this, fisherman,” she whispered. “At least I chose my child.”

He turned his back on the witch with a halo of lantern light. He took the first step home through the snow, then the second.

He held Maisy close. Her small frame was already exhausted from shivering. She slipped purple fingers, still streaked with clay, under the cuff of his sleeve.

“It creeps, Papa,” she whispered. “The cold, it creeps.”

About the Author

Kelsey Hutton

Kelsey Hutton is an Indigenous Métis author of speculative fiction from Treaty 1 territory and the homeland of the Métis Nation, also known as Winnipeg, Canada. She loves reading and writing in lots of different genres, but particularly historical fiction, fantasy, and space opera.

Kelsey was born in an even snowier city than she lives in now (“up north,” as they say in Winnipeg). She also used to live in Brazil as a kid. She tries to appreciate the clean, cold winters, but mostly misses the beautiful wide-open lakes of summertime. When she’s not beading or cooking, you can find her at KelseyHutton.com or on Twitter at @KelHuttonAuthor.

About the Narrator

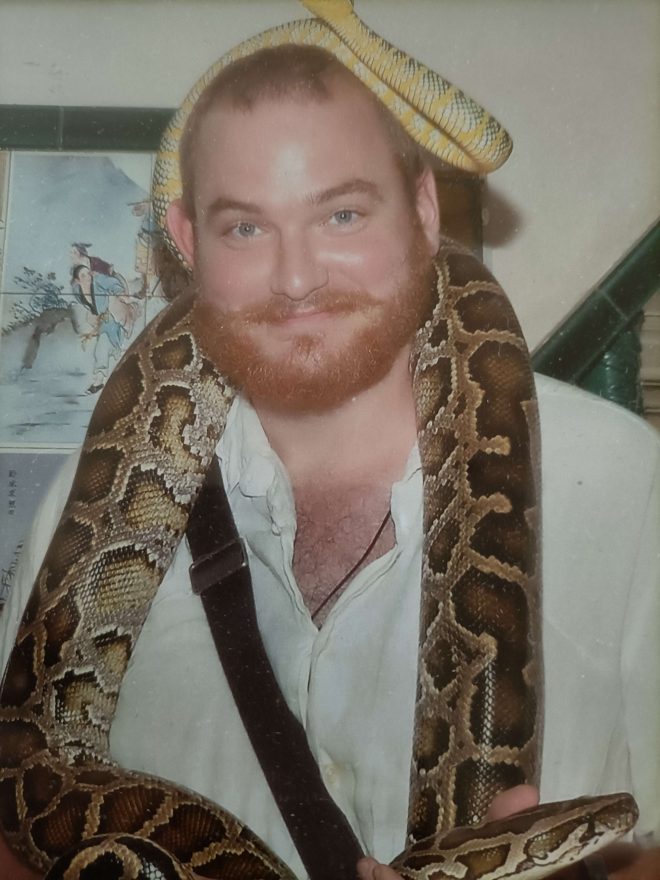

Ed Gamble

Ed Gamble (he/him), whose massively out-of-date bio picture shows him holding snakes for some reason, is a teacher living in east London. Having lost the fight with the capital’s horrific gravitational pull, he has lived there for nearly a decade now, teaching teenagers to despise Shakespeare, poetry, and the limitations of the British educational system in general. He is truly honoured to get to read things out for internet people, as that is probably the next logical step in a career in literature education.