Cast of Wonders 561: All Good Children Come Out To Play

All Good Children Come Out To Play

by Karlo Yeager Rodríguez

For longer than I could remember, we had been Lázaro and Marta. We should have been celebrating our ninth birthday together.

Instead, my twin brother was laid out on our table. He looked so small and still and pale: the silent point around which our family and neighbors swirled, dancing and singing and laughing. Abuela Trini held me in her lap and cradled my head in the crook of her arm. Her reedy hum meandered through the cuatro music until my tears dried and my sobs shrank to hiccups.

I never meant for any of this to happen when I slipped away to bathe in our secret pool the day before. The one only Lázaro and I knew about, the one nestled in a clearing up the mountain and surrounded by yagrumo trees, the one we had splashed around in, the one with chilly spring-fed waters, the one where the freshwater shrimp tickled our legs and nipped at our feet.

All I had wanted was to be alone.

It was important to welcome a new year of life by washing away all traces of the old, but my insistence on doing this by myself had wounded Lázaro.

“It’s my birthday, too,” he said, after I made him promise not to follow. I left him sulking where the footpath began its ascent.

I had hung my clothes on a branch to keep them clean. My dress and underclothes floated, pale as ghosts against the greenery. I sighed my way into the chill of the water and let the imperfect quiet of green and living things flow over me.

At least until Lázaro showed up. At first I pleaded with him to go back, to leave me be, but this only made him laugh at me from the water’s edge. He snatched my dress off the branch, holding it up against his body, taunting me by repeating everything I said in a falsetto. I stormed out of the water, dripping, too furious to bother covering up my nakedness anymore and shoved him.

The moment stretched: a breeze whispered through the trees and the yagrumos flashed the silvery undersides of their leaves as my brother slipped on one of the boulders. The wet crack his head made when it bounced off another rock sounded so, so far away.

I have no memory of how I got back home, wide-eyed but unable to cry, or even speak, to confess what I had done.

Now, I was alone.

Now, because of me, the day we should have celebrated our entry into the world would instead be marked by one of us departing it. One day for the search party to pull Lázaro out and bring him back; another to watch over him and pay our respects; and on the third day, we would surrender him to the town priest for burial.

Along the frayed edges of where Lázaro had fit into me was an ache, a dull pain where he’d once been. Who would I become once that wound healed? How does anyone learn to live without half their soul?

“Why am I the only one crying that he’s gone?” I asked.

“Dry your tears, Martita.” Abuela Trini stroked my hair. “We may offer up the tearful faces Padre Eusebio expects at his service, but today we are also glad your brother has escaped this all the pain and heartbreak of this world.”

Families from the neighboring hills cane straight from the cane fields, company whites still smudged green from the day’s work. They bowed their heads over their palm frond hats as they shuffled past my brother. A cluster brought their drums, while other workers left their machetes leaning against the door jamb to join in the dancing.

“Come, come. . .no more tears.” Abuela said when I gave a long, shuddering sigh. She smoothed hair from my brow, her hand dry and leathery from back when rolling tobacco made good money, before sugar became king. Trying to obey her wishes, I thought about when Lázaro and I were younger and each pretended to be the other to see if anyone noticed. When I remembered that no one ever caught us–not even Abuela Trini–a shaky smile emerged. “That’s it. Rejoice that tonight, Lázaro flies through the door of the moon and to the other side of the sky.”

Mami let the drums pull her away from the town priest and swirled her skirts as she danced. Papi was working his shift, hacking sugar cane because the majordomo hadn’t given him leave for Lázaro’s wake, much less his funeral.

When the priest cast his gaze about, Abuela Trini slid me off her lap. Someone needed to arrange for my brother’s transport and burial in the town graveyard.

When Lázaro had been gone almost four months and with Mami’s pregnancy starting to show too much for her to continue working, Papi alone couldn’t earn enough to keep us all fed. I took my brother’s place working the fields. I’d helped loading the carts at first, but with the zafra falling behind schedule and threatening to spoil, they needed every hand available cutting, no matter if they knew how. Hours swinging a machete under a merciless sun. It’s what I deserved and after the first few weeks, my blisters had toughened into calluses. After weeks of this, pain smoldered deep in my muscles and bones, flaring up and making my hands tremble whenever I needed to do anything more delicate than hacking.

Like attempting to sneak an offering of tobacco leaves onto the shrine I’d built with Abuela Trini for Lázaro, for instance. My hand spasmed, scattering the sheaf all over the dulce de coco Abuela Trini had made. She turned and shot me a look before she gathered the dried leaves. With a few deft movements, she tucked them back into a bundle and tied them together again.

“Here,” Abuela Trini said, handing it back to me. When I didn’t move to take it, she glanced at my hands. I clasped one hand within the other to lessen the throbbing pain.

“After we’re finished here, let me teach you how to hold your machete the right way to cut cane.” She placed a wreath of blood-red hibiscus flowers around Lázaro’s cédula papers, his mark scrawled at the bottom of the parchment. Abuela Trini had tried so hard to teach him his letters so he could at least write his name, but it never took. She fussed over the sheaf, fanning it out before she caught me looking.

“You think I didn’t know?” She quirked her lips.

The moon was a phantom crescent framed in our doorway. If Lázaro was watching me, peeking around the edge of the moon, I didn’t want to speak for him when he no longer could. When he was alive I could always count on him to keep my secrets. I thought it only fair that I kept his in turn.

We had stolen Abuela Trini’s tobacco, but when the time came, Lázaro teased me because I hadn’t dared try it. Ignoring my warnings, he stuffed the whole wad into his cheek like he’d seen our grandmother do and chewed on it until he dry-heaved. Even now, my gorge rose as I recalled the smell of bile emerging from his open mouth in a thin rope to mix with the dust of the chicken yard.

When Abuela Trini called for Lázaro to help her, he wiped at the sick on his chin and did as he was asked. She initially asked why he looked so pale, but Lázaro insisted he felt fine. So, for the rest of the day she acted like she didn’t notice how sallow his skin looked and kept giving him chores. He drew water from the well, and carried it to her, cleaned the chicken coop, and oh, hadn’t he gathered enough eggs to trade with the Sánchez family over on the next hill in exchange for some salt cod?

Defiant to the end, he hadn’t complained once. He never let her know he was sick until I pleaded with Abuela Trini to stop, Dios mío, please stop.

“Well, do you?” Abuela Trini’s question made me flush.

Rather than meet her gaze, I looked at the shrine we’d built for Lázaro. It didn’t seem enough, just a small table with the only photograph we had of him flanked by two candles and surrounded by a wreath of hibiscus. Within the circle was a glass of water and a plate holding the tobacco and dulce de coco. The only two things we knew he’d liked in life.

“He said you gave it to him.” My cheeks blazed at the lie.

Abuela Trini scoffed. “And you believed him? After all the times he tricked you?”

“I just saw it as part of who he was.”

Abuela glanced at me, smiling.

“He was something,” she said. “Wasn’t he?”

I ran a finger around the edges of the ofrenda instead of meeting her eyes. Would any of this help us see Lázaro again?

As if in answer, Abuela handed me a basket and pushed me towards the chicken coop. Pushing my hands under the clucking hens to take their still-warm eggs, I was reminded of our favorite game, trading places, dressing in each other’s clothes and how we had fooled everyone.

I realized with a pang we wouldn’t have been able to play that game for much longer, with the way our bodies had started to change. Another ragged hole where something used to be.

I kicked up clouds crossing the chicken yard on my back to the house, dusting the eggs in my basket. Abuela was outside taking with the priest from town.

When he mentioned holding a memorial mass for Lázaro on the Feast of Holy Innocents, the mere reminder that it would mark the anniversary of his death reopened that hurt all over again. It used to be an important day for the both of us.

Our birthday.

We were tucked away in an overgrown corner of the cemetery for the graveside service, tall weeds poking up between the headstones. Sweat trickling in the blaze of late afternoon, I struggled not to fidget. I had already endured Mami snapping at me when I chafed at wearing my best dress during our two-day ox-cart ride into town. Behind us, the men chosen to carry our patron saint in festival procession stood in solemn silence. Santa Juana’s statue peeked over their shoulders, her Taíno features severe as she sheltered children huddled under her embrace.

When the ceremony was done, Papi joined the men in putting their backs into pushing Santa Juana’s bier. With the priest in the lead and bier rolling behind him, our procession wended its way from Lázaro’s graveside, through the overgrown parts until we passed the shining marble crypts of the moneyed families. We walked through the tunnel connecting the graveyard to the cobbled streets of town, gathering festivalgoers and worshippers carrying baskets with dolls in them.

A handful of people in painted coconut masks fell in with us, stalking around the edges of the crowd. The person who wore the crowned and bearded King mask capered and pantomimed sending his guards among the others. They searched among the baskets carried by many, tasked with finding the hidden Baby Jesus doll before the procession reached the cathedral steps.

Abuela Trini had once told me the festival celebrated on Lázaro’s and my birthday was to honor the children slaughtered by wicked King Herod. Up here in the hills, though, people believed something different. Niñito Jesus interceded when he found out, and out of remorse He’d made a special place for the souls of the innocents who had died in his stead that day.

Abuela Trini’s hand in mine, I noticed other children nearby trying to look dignified but managing only boredom. We traded looks and, in that wordless way children share, agreed we were all friends–for at least long enough to slip away and find somewhere to play together. I squeezed Abuela’s hand and she nodded her permission.

I led my new friends back to the quiet and overgrown part of the graveyard to make sure Lázaro didn’t feel left out. We ran through the tall grass, weaving between the gravestones in the lengthening shadows. Our whoops and peals of laughter died against the stones of the town’s high wall–and the air of the graveyard, now still and cool as the surface of a hidden forest pool, swallowed up our cries. Music from the festival flowed over the wall to us, as faint as if played from the next world.

We played among the headstones, stopping to call the names carved into them to join in our games. After circling them once, twice, three times, we chose who among us would be it in sing-song:

Tín marín de dos pingües

Cúcara mácara, títere fue

¿Cuantas patas tiene el gato?

Un, dos, tres y. . .CUATRO

I circled behind the girl who was it and hid behind a headstone so old its name had worn away. She counted aloud; her eyes scrunched closed. By the time she reached ten, the last sliver of the sun had slipped beyond the edge of the world.

Night fell, the sky dark and moonless.

Where the moon should have been, a deeper darkness gaped in the night sky, the pale stone of the moon rolled aside. The door to the other side of the sky lay open.

The girl gave up trying to find us and called to reveal ourselves. I stood and stepped out to see new children, pale as moonlight, appear in the long grass. There were many more than had started the game.

Motionless, we living children looked from one to the other, trying to take their measure. It was one thing to call them in play; quite another when they appeared. We tensed, uncertain.

The ghost-childrens’ wan, bloodless laughter broke the spell and without anyone speaking a word, I knew the game had shifted. Instead of hide-and-seek, we were now playing tag. I turned, ready to run.

A pale, cold hand closed around my wrist.

Lázaro’s.

His fingers shone against my brown skin. I ached to turn towards him, a joyful welcome on my lips.

“Don’t,” Lázaro said, and it was, it was his voice! “Cierra los ojos.” I squeezed my eyes shut, even when I could hear the trickle of stale water, smell its rot.

“Ready?”

I nodded, bracing myself, but still gasped as my twin brother poured into me, a chill soaking my flesh, seeping into my bones. He clambered into my skin, curled and entangled with me.

“Lázaro?” I blinked. The other children who had also been caught by their silent playmates rubbed their eyes as if waking from disheveled dreams. They turned towards us as one, eyes gleaming with a cold light.

“Go!” Lázaro’s words hissed out of my mouth. “Back the way you came. If they catch me, they’ll send me back. Now!”

The other children converged, almost surrounding me. With them in pursuit, I sprinted through the cemetery and up, up, up through the narrow tunnel. When I came out onto the small plaza on the other side, I slipped on some crushed palm leaves and carnations the procession had left in its wake.

The plaza and street were almost empty, with only a few stragglers here and there. Ahead, the tail of the procession was turning a corner, still making its way uphill to the cathedral.

“Let’s catch up with them,” Lázaro said with my own voice. “We can blend in with the crowd, use our stronger connection to wait them out.” I ignored the people nearby who thought I was talking to them, leaving them with words still in their mouths. Behind me, the other children burst out of the tunnel, paused long enough to see me and, as one, kept up the chase.

Panting, I turned a corner, almost at the tail of the procession. The masked figures lurked around the edges of the crowd, the King commanding his guards with a gesture. To avoid having their doll snatched away, the men and women held their Moses baskets aloft and out of the guards’ reach. Ahead, the church bell rang and rang and rang, calling the town to mass, and the procession to its destination.

“Watch out!”

I flinched at Lázaro’s warning just as one of the girls from the cemetery shrieked past, slipped and tumbled to the cobbles. She picked herself up again, swaying a bit as she stood. The pale light flashed behind her eyes and was gone, leaving her to blink at me in confusion. My breath sawing in and out of me, I turned to squirm my way through the crowd. I ignored protests from people I pushed aside, sparing panicked glances at the ground to avoid falling.

Ahead, Santa Juana towered over the procession, close enough to see the thin gold wire of her halo gleaming in the lamplight. The cathedral loomed, its open doors within sight. We were close, so close. Laughter I wasn’t sure was fully my brother’s bubbled out of me.

“Vamos,” Lázaro said. “This will be easier than stealing Abuela’s tobacco. Remember?”

The masked King Herod figure burst into our midst, people backing away from him with cries of surprise. Unable to keep pace, I was left stranded with him looming over me. Hunched, his crowned mask turned this way and that, peering at everyone’s faces before finding mine. He bent closer to look into my eyes before he capered, pointing at me with one hand, gesturing for his guards to capture me with his other.

I froze, stomach clenching. Even Lázaro, so quick with his words, fell into dismayed silence as the tall figures drew closer, arms extended to snatch us away.

A flash of movement broke the spell, and another of the dead-eyed children lunged at me. I spun away, crowing as his fingertips grazed the swirl of my skirts and closed on empty air.

I spun too close to the King and his entourage, who stilt-stepped away too fast until, windmilling his arms, crashed into his guards. They collapsed; the dead-eyed child squirming to get out from under a heap of limbs.

At last, we came alongside the bier, rumbling along. Papi was at the head, pulling while the men farther back helped steer. Santa Juana’s fierce gaze was fixed on some unseen danger ahead, ready to protect the children huddled against her.

I pushed aside heavy velvet draped over the sides to crawl into the dark, narrow space. The bier swayed as Papi and the other bearers pushed it.

“Great spot.” Lázaro filled my nose with the smell of water flowing over stone. “They won’t see us until it’s too late.”

The bearers’ footfalls and grunts of effort echoed around us. Could they hear us? “I’ve missed you,” I whispered, just in case.

“You want me to stay?”

“How else can I ever make it up to you for–” I tried to confess at last, to take the first tottering steps towards forgiveness but the remaining words were like stones piled on my tongue. Sharing the same space, did he already know what I wanted, what I needed from him?

The bier slowed, rumbled to a stop.

“We were once one,” I said, reaching for the next words. “Made two. Right?”

Lázaro made a small noise in the dark before speaking.

“Both of us in the same body, at the same time?”

Already I was cramped in my own skin, shoved aside in the little time he’d been back. I couldn’t say why I was surprised with the way he had always hogged our hammock.

“Remember our game?” I asked. “Wouldn’t it be fun to fool them again?”

The thunk of the brake levers locking made me jump. I pulled aside the fabric to peek outside. Part of the cathedral was visible through the crowd, and I realized Mami must be waiting for me at the top of the steps, sharpening her words for whenever I showed up again.

“I’ll get more time with Mami and Papi?” Lázaro asked.

I nodded, thinking of Mami and realizing he couldn’t know, said, “Yes, and your baby brother.”

“Brother?”

“Could be a sister, but Mami’s sure it’s a boy.”

“Marta,” Lázaro said in a small voice, “Why are you doing this, being so good to me?”

“I told you already. I miss you.” I rubbed at my eyes with the heels of my hands. “I wish I could take it back, what happened. I wish you’d had more time with us, with me.”

Lázaro’s chill receded for a moment.

“What do you say?” My chest ached, waiting for his answer.

“You know you’ll get to find out what’s on the other side, don’t you?”

“I guess,” I said. I thought about saying more but didn’t know how to begin. “Help Abuela Trini keep the shrine and come look for me among the gravestones next year.”

“You ready, hermanita?”

“Little sister?” I made a rude noise. “I was born first.” Before I could think about what I was doing anymore, I jerked aside the cloth, and stepped out–

Into the impossible brightness of a mid-day that was not, transported from the night-time festival to the shore of our shared place, the secret pool of our memories, even now, the breeze setting the yagrumo trees to whispering among themselves. Far-off birds called to each other, and the quiet rill of water flowing over the immense rounded stones made them glisten.

Lázaro rose from the pool, water streaming off him.

Mud smeared his teeth and freshwater shrimp squirmed in his hair as he waded out. I moved towards the water’s edge, towards his haunt.

“I’m–” I stammered, looking at my hands rather than at the ragged edges of where his eyes had been. He took my hands, and guided me into the water, shushing me. Underwater, the shrimp nipped at my toes. “Can you forgive me?”

“Hermanita,” Lázaro pressed a finger to his mouth. “Don’t spoil the fun.”

Please, I wanted to ask, but waded past him. First to my waist, then, flinching, to my chest, the cold stealing my breath away.

Submerging, I felt the tug of our mingled souls, pulled North and South, drift apart. Lázaro would stream into my body and wake, blinking, on the church steps while I kicked through the deeper water, a thousand feather-light caresses trailing across my skin. Shrimp peeked out from rocks, feelers like finger tickling as I kicked into the dark. Lungs burning, I wanted to glance back, wanted to wish my brother luck, but ahead, light slanted through the water, and I kicked and kept kicking against the cold dark until I could splash out into the glory of light and air once more.

Host Commentary

We remember our dead in many different forms and traditions, but in just about all of them we seek to recall human moments and joys. Laughter and love. Bravery and belonging. A continuation of the spirit, carrying forward the lives cut short into our own existence, telling them they are loved, they are remembered, they are still part of us. It’s a reminder that the sharpness of grief only wounds us when our hearts are full, and that though our grief is part and parcel of being mortal, the joy and love we share is eternal, and enduring.

About the Author

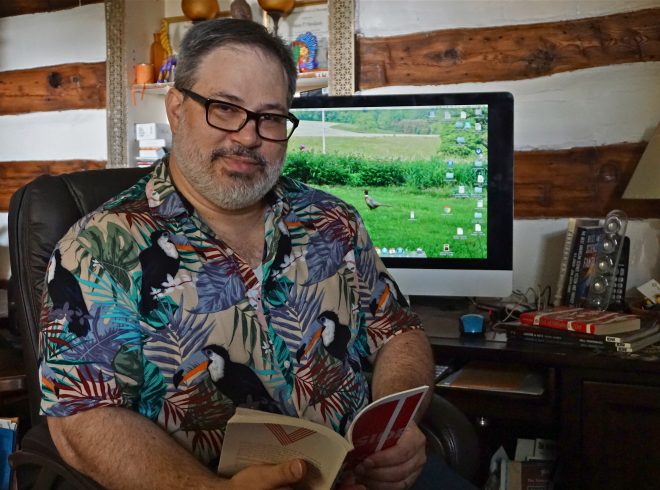

Karlo Yeager Rodríguez

Karlo Yeager Rodríguez was born and raised in Puerto Rico, but now lives near Baltimore with his spouse, a grumpy dragon, and one odd dog. His writing has appeared in places like Nature, Uncanny, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, and is forthcoming in Speculative Fiction for Dreamers: A Latinx Anthology. He’s also on Podside Picnic, where he discusses his genre (mis)education with his co-host, Pete.

About the Narrator

Sofia Quintero

Sofia Quintero is a writer and producer who tells stories that meet audiences where they are and take them someplace better. Raised in a working-class Puerto Rican-Dominican family in the Bronx and graduating from Columbia University, the self-proclaimed “Ivy League homegirl” has published six novels and twice as many short stories across genres including YA, “chick lit,” and erotica. Under the pen name Black Artemis, she wrote three novels described as “sister-centered hip-hop noir.”

Sofia’s stories are usually ahead of the curve, offering nuanced depictions of underrepresented communities years before the mainstream entertainment industries took up the challenge. Because her novels reflect an intentional hybrid between the commercial and the literary, exploiting popular tropes to raise socio-political issues for broad audiences, they are assigned at colleges across the nation and in multiple disciplines including English, Sociology, Women’s Studies, Criminal Justice, Latino studies, African American Studies, and Education.

In 2012, Sofia earned an MFA in Writing and Producing Television from the TV Writers Studio at Long Island University and was a 2017 Made in NY Writers Room Fellow. In addition to developing several projects for television, she’s working on her seventh novel called #Krissette. Inspired by the #SayHerName movement, #Krissette will be published by Knopf Books for Young Readers in 2020. Sofia will also be re-releasing her Black Artemis backlist as audiobooks.