Cast of Wonders 539: Little Wonders 39 – Home Ties

Park’s All-Night Ramyun and Snack Emporium

by Seoung Kim

After the stoplights go to flashing red and the bars make their last calls, Park’s All-Night Ramyun and Snack Emporium lights up, its warm yellow lanterns beckoning customers from the street.

The tiny dining area just outside the truck is already full: a rusalka who always leaves the counter wet; her girlfriend Ms. Llorona, who uses too many napkins crying but refuses to order less spicy noodles; the old yokai lady Mrs. Rokuro with her mile-long neck; and a jiangshi who isn’t eating but stares at every drunk club-goer who stumbles down the street.

Yujin Park crosses their arms and leans back on the freezer, checking their phone for the fiftieth time that shift. It seems like everyone is out enjoying the last summer before senior year — except for them. Their feed is full of rooftop parties and group selfies.

Even if they could escape from the drudgery of scrubbing moldy drains, the thought of showing up covered in a thick layer of grease is too mortifying to bear.

They’re drawn out of their thoughts by the sound of a throat being cleared. An imugi waits at the counter, scales bristling. Yujin begins haltingly taking his order before he gestures with a claw for the elder, more fluent Mr. Park.

“Ah, annyeonghaseyo,” Appa says, dipping his head, and the two of them launch into conversation. Appa’s voice is louder in Korean, smoother and more confident.

Yujin’s appa tends to treat gender lightly. Tonight, he’s taken the appearance of an older woman, black hair streaked with gray tucked into a bun at the base of the bandanna covering his head. No matter what form he takes, his face has a sly, narrow look to it, something all of his children inherited.

Yujin slouches back against the freezer, trying to squeeze themself out of the way. They catch snatches of English words like “business expenses” and “proprietorship.”

Eventually, the imugi decides he wants to eat more than talk, and Appa ladles some broth on top of a bowl of noodles and passes it to Yujin for the toppings: thick slices of chashu, eggs soft-boiled in tea, kimchi and scallions and beansprouts. Steam from the broth, fragrant and rich, billows up in a cloud that fogs Yujin’s glasses.

“Kamsahamnida,” says the imugi as Yujin hands him the bowl, and they mumble in return.

As he leaves, Mrs. Rokuro ambles up to the counter to return her soup bowl and chopsticks.

Mr. Park nods to her. “Thank you for coming,” he says, and she opens her mouth and makes a noise like metal scraping glass. “Oh, of course! Yujin, could you walk Mrs. Rokuro back to her apartment?”

Yujin looks up at Mrs. Rokuro, whose head is making gentle figure eights above the truck, her long white hair swaying in the wind.

“Dad?” they say. “Can I talk to you for a second?”

The two of them shuffle away from the serving window into the back of the truck. Mr. Park puts his hands on his hips, waiting for Yujin to speak. Never a good sign, but Yujin takes a deep breath anyway.

“I don’t want to walk her home.”

“Why not?” Appa says.

“Can’t you do it?” they say, and the note of desperation in their voice pinches between their father’s eyebrows.

Mr. Park sighs. “Mrs. Rokuro has been here since my grandfather moved to the city. She was one of my first customers,” he says.

“But what if– what if–”

More than anything, Yujin is afraid of running into someone from school while taking the old lady home.

Mr. Park reaches into his apron pocket and produces a large pearl with a rainbow sheen — a pearl of knowledge, something every gumiho guards closely.

“Take it. You can contact me with it if you’re in trouble.”

Yujin hesitates a moment before accepting the pearl, cradling it in their hands like an overly full bowl of soup. It’s heavy and warm in their palms.

“…Trouble?” says Yujin.

“Bad guys.”

“What if I lose it?” they ask.

Mr. Park begins steering them out of the cart. “Then call me on my cell.”

Mrs. Rokuro’s place is a few blocks over. As the two of them walk beneath the high rises, Mrs. Rokuro’s head occasionally skims up the side of a building and slides into an open window, causing someone to scream, at which point Yujin tugs on Mrs. Rokuro’s arm to get her to move on.

They pass a group of dokkebi and a couple of werewolves, probably stragglers out past last call. The bass thumps of a speaker sound in the distance. Above them, the skyscrapers are mostly dark. They’re about to turn the corner when-

“Yujin Park!”

Yujin goes cold with fear. Someone recognizes them. They can see the headlines now, splashed across the school paper: ‘Local Loser Parties With Grandmas.’

“Hey!” Miguel Hernandez strolls up to them, dressed in a devastating black crop top and jeans, smiling broadly. The brujo is part of this year’s graduating class, one grade above Yujin’s. “You going out?”

“Hah,” says Yujin. The noise is only a little forced. “No, just walking a customer home.”

“Mrs. R,” says Miguel respectfully. “You look nice tonight.”

She grins at him, her pointed teeth glinting. Slowly, Yujin’s fear begins to melt into relief.

“Your dad’s place is an institution,” says Miguel. “Can’t get good liver ramen anywhere else.”

(Liver ramyun with shoyu broth and extra corn— that’s what Miguel always orders. Yujin tries to give him the best liver pieces.)

“Where are you headed?” they ask.

“Open mic with the boys,” says Miguel.

Yujin suppresses a stab of longing — Miguel’s poetry is famous for bewitching entire crowds.

“I heard you broke up with Luna,” they say, trying not to sound too hopeful.

“Yeah, it was more of a mutual thing… we’re both going to out of state schools, and we didn’t want to do long distance.” Miguel looks sheepish. “How about you? You graduate next year, right?”

“Right,” says Yujin.

“You’re not excited?”

They look at the ground. “I can’t decide what I want to do.”

“I hated when people asked me, too,” says Miguel, clapping Yujin on the shoulder. “So I won’t. Do whatever, little buddy.”

The heat from his hand seems to be spreading to Yujin’s cheeks. They swallow. This is their last chance.

Yujin fishes a pre-punched card out of their apron pocket. Good for one free bowl of noodles. “Here. Stop by when you’re back in town.”

“Oh sweet, thanks!” he says.

Yujin can only manage a vague affirmative noise.

“Good luck. I mean it. I’ll see you around.” With that, Miguel vanishes in a cloud of purple and silver smoke.

Yujin stands there for a moment, watching the space where he disappeared, already lost in imagining Miguel’s return. They would slide him his order, maybe with their phone number on the receipt– no, wait, it was a free bowl, so there wouldn’t be a receipt–

Mrs. Rokuro begins making her slow progress along the sidewalk again, and Yujin hurries after her.

They eventually reach a dead end. Smoke issues out of a lone manhole where the pavement turns to scrubby grass. Most of the streetlights are busted, only one still flickering overhead.

“Um… you live here?” Yujin asks.

Mrs. Rokuro jabs a long, white finger in the direction of Yujin’s pocket.

They pull out the pearl. “This?”

She places her hand over it so that both of them are touching the surface, and the pearl begins to glow.

Yujin almost drops it in surprise as a memory fades in: Mrs. Rokuro as a young woman, her hair still black, tagging along in a parade of yokai down 5th avenue. Kappa and tengu and even gumiho, shrieking and cawing and banging drums.

The band of yokai carry lanterns and instruments, but Mrs. Rokuro’s hands are empty; she trails behind at the outside of the crowd, her neck snaking down alleyways and occasionally getting caught on a lamp post. No one seems to be paying attention to her.

Yujin sees the images as though through a fog: when the band comes to a side street, Mrs. Rokuro breaks away, wandering until she comes to a familiar cart.

Mr. Park, looking only slightly older than Yujin, greets her with a smile. He piles tteok-bokki into a paper basket and hands it to her, and she takes a seat at the counter. She sits and eats while he wipes down bowls and chatters at her, asking her favorite flavors and snacks.

Appa always worked hard to make the cart welcoming. The additions to the menu over the years were usually because of a specific customer:

“Here,” Appa would say, holding a bit of black-skinned chicken in his chopsticks, “try this, Yujin. It’s for Mr. Liczyrzepa.” The oi muchim ramen was for a kappa from Brooklyn.

Watching the two of them, it’s hard for Yujin not to smile. The bowl Appa eventually invented for her was extra long soba, chilled with pickled radishes.

The image dissolves, leaving Yujin and Mrs. Rokuro standing in the street together. She nods to them, her neck looping over itself with the motion. Yujin bows politely in return.

Then Mrs. Rokuro wrenches off the manhole cover and slithers down. When the last of her neck disappears beneath, a white hand reaches up to pull the cover back into place.

Yujin turns back toward the truck. In the hours before dawn, the streets are lit pale blue and limned with gold. They’ll have to ask Appa about the first time Mrs. Rokuro visited him– how did she know about the pearl? Did she really live in the sewer?

Maybe Mrs. Rokuro was trying to thank them for walking her home, and for everything else.

They see the orange light of the cart from a few blocks over, the smell of simmering broth thick in the air. Grinning, they break into a run, dodging bus stops and traffic cones, winding their way through the city sidewalks, nimble as a fox. The pearl, tucked back into their apron, is still glowing.

Minor Magics of Chinatown

by Wen Wen Yang

I hefted the bulky envelope and stared at the return address. Wellsley college.

Well, damn.

They don’t send heavy packets to rejects. I didn’t even need Cousin Lei’s red-envelope-telepathy to tell me what it said.

The rest of us held our red envelopes up to the light to see what bills were inside. Cousin Lei would rub it between his fingers and just know.

At dinner, I told my mother, “I got into Wellsley College, in Boston.”

“Boston is too far.”

That night ended with a slammed door. I furiously wrote in my journal, “Even if she doesn’t give me permission, I’m going.” I drew stars enclosed in circles around that sentence as if I could force my future into place.

When I woke, my puffy eyes made my monolids even more pronounced.

I pressed a hot towel to my face and wanted to scream into it. Instead, I silently accompanied my mother to the Chinatown farmer’s market. We moved like choreographed dancers. She stayed a couple steps ahead of me while I pushed the rolling cart.

A Coach handbag, First Auntie’s latest gift, hung from her shoulder. First Auntie could tell a counterfeit from authentic without touching the leather goods.

“How much?” my mother asked in Mandarin.

The vendor told her the price. My mother weighed the mangos in her hands.

Her father was a grocer so I don’t think her abilities came from magic. Her hands learned from years of sorting the fruits and vegetables. She never brought home mangos with internal brownness. Her grapes were always plump and sweet.

She couldn’t find a red delicious apple that was worth buying because that name is a lie.

My mother countered with a lower price.

Thankfully, this wasn’t Macy’s.

One winter after I’d hit my growth spurt, we couldn’t deny my need for a new winter coat anymore. The sleeves couldn’t cover my wrists and the jacket looked cropped. At Macy’s, my mother ripped the tag off a J. Lo winter jacket, the last one in stock. She hoped the store would find a lower price on the computer. The Macy’s store clerk must have come from similar people, telling my mother that whatever the price turned out to be, she should buy it. Because I looked like J. Lo in it. We’re both from the Bronx, but that’s where the similarities end. My mother didn’t know who J. Lo was, though we did buy the jacket. I was going to pack that coat for Boston’s winters.

The fruit vendor looked at the mango in my mother’s hand and countered with another price.

I thought it was fair.

My mother offered another price.

I sighed loudly.

My mother shot me a look.

The fruit vendor laughed, “Ok, for you. Your daughter doesn’t like haggling?”

“She’s too American,” my mother said, her fingers sliding over mangoes.

I added the bag, it felt like five pounds, to the rolling cart as she paid.

“You should learn to do this,” she told me in her city’s dialect. “I can’t always be shopping with you.”

I started to say “Does that mean–” when a woman by us exclaimed my mother’s name in our dialect.

My mother turned and greeted a woman with a bright round face. She introduced me and I greeted Auntie Xi who had worked with my mother at the sweatshop, excuse me, garment factory.

“Wow, she’s so tall!” Auntie Xi looked at my mother like she had overwatered me. I felt like I was wearing the too small winter coat again. “How old?”

“Seventeen.”

“Off to college soon.” Auntie Xi then turned to me and asked in English. “What school are you going to? NYU? Columbia?”

Even people who just met me assumed I would stay home.

“Wellsley College, in Boston.” This felt more real than getting the thick envelope, full of forms and futures.

My mother’s eyes widened but managed to smile when Auntie Xi explained, “You’re letting her go to Boston! She will marry a Harvard student. My son’s going to Chicago for engineering…”

I exited the gossip train and went in search of bubble tea.

My mom found me at the small seating area by the food trucks. She added a golden pineapple to the cart.

We made several more stops, Vita Tea in Lemon Tea, a copy of the World Journal, until the cart was heaped with goods. We rode the screeching subway home without speaking as the announcers mumbled. When we had put away the groceries, she reappeared with the acceptance packet.

She set it gingerly in front of me. I pointed out the financial aid information.

“It’s out of state tuition, but I will get a work study job, and I have savings–.”

“Only girls in the pictures.”

“It’s an all women’s college, next to Harvard.” I silently thanked Auntie Xi for reminding me of that point in its favor.

“You want to go, you go.”

I blinked up at her. “I can?”

“I saved money for your college too. Your college is in Boston.”

I beamed up at her and quickly wrote the check for the first semester before she could change her mind.

“Besides, whatever Auntie Xi says, happens. You’ll find a husband at Harvard.”

I looked into the gift horse’s mouth. “Could Auntie Xi say I was going to win the lotto instead?”

My mother waved her hand as if sweeping away that crumb. “She’s only good with marriages, not money.”

I shrugged.

My mother beamed, “And Auntie Xi said there is a Chinatown bus to Boston. You can come home every weekend.”

Even the magics of Chinatown could only loosen my leash, not sever it.

Host Commentary

Just like a late night bowl of your favourite takeout, this story is rich in comfort and flavour. It shows us a community drawn together by a sense of welcome, where individuality is honoured. We also see, in Yujin, the uncertainty, pride and unease of the young adult, one who still doesn’t quite know who they are or what they want. Family and community are a support network around them, but also kinda lame. Finding the opportunity to be seen as an adult and doing their own thing creates conflict there… but over the course of this single evening, Yujin learns some of the value of their family ties, as seen by others both old and young. This story creates a gentle sense of newly discovered maturity, and with it, the feeling that the world is out there waiting, and Yujin is ready for it.

Some families hold tighter to their children than others, and the protagonist of this story definitely starts out ready to fight tooth and nail for her independence. The big argument isn’t slow in occurring, and ends with mother and daughter each determined to have their way. In the aftermath, continued expectations and disapproval are conveyed silently, and on both fronts mother and daughter use the social ties of the community to continue their dispute. And yet…in the end, expectations are adjusted, disapproval shifts to pride, and if the home ties are very much still there, hopefully they’re a comfort and support in this case.

For all of you taking your own first steps into independence, I hope your own home comforts will always be there when you need them.

About the Authors

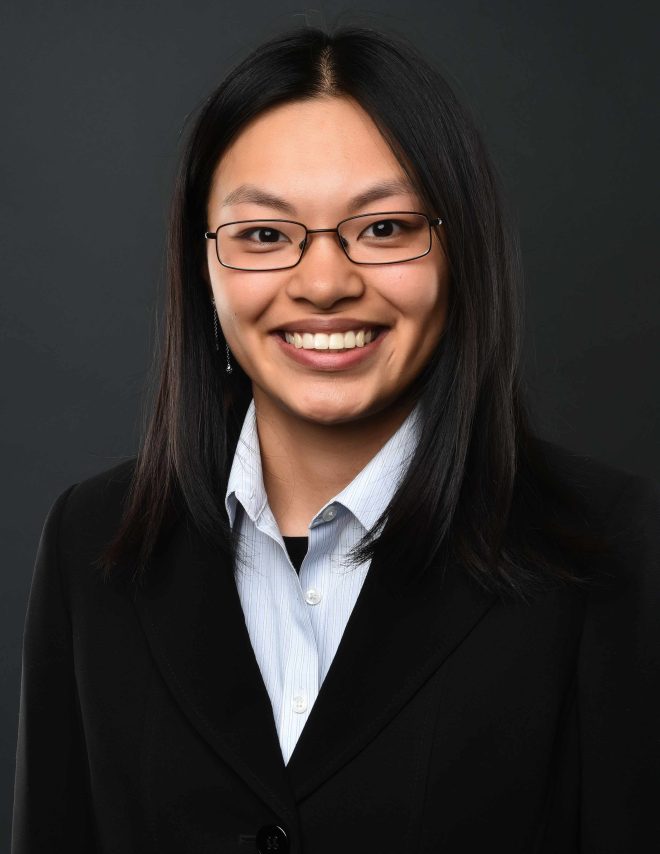

Wen Wen Yang

Wen Wen Yang is a first-generation Chinese American from the Bronx, New York. She graduated from Barnard College of Columbia University with a degree in English and creative writing. You can find her short fiction in Fantasy Magazine, Zooscape, Fit for the Gods and more. An up-to-date bibliography is on WenWenWrites.com. She listens to audiobooks at three times speed, talks almost as fast, and misses dependable public transportation.

Seoung Kim

Seoung is a Korean librarian who loves reading and writing stories with queer Asian protagonists. In their spare time, they can be found hiking in the woods or haunting the aisles of craft stores. You can find his published work on seoungkim.com, and he tweets @chimneyfalls on Twitter.

About the Narrators

Isabel J. Kim

Isabel J. Kim is a Korean-American speculative fiction writer based in New York City. She is a Shirley Jackson Award winner and her short fiction has been published in Clarkesworld, Lightspeed, and Strange Horizons, among other venues. When she’s not writing, she’s either practicing law or co-hosting her internet culture podcast “Wow if True” — both equally noble pursuits. Find her at http://isabel.kim or @isabeljkim on twitter.

Rebecca Wei Hsieh

Rebecca Wei Hsieh (she/her) is a NYC-based Taiwanese American actor and writer who feels awkward writing about herself in the third person. Her acting work encompasses voiceover, stage and screen. Her writing has been featured in outlets like We Need Diverse Books and Wear Your Voice Magazine. She has a BA in theatre and Italian studies from Wesleyan University, and is currently co-writing a memoir about Tibet. Her website is rwhsieh.com and you can find her on social media @GeneralAsian